EYFS: How to get home visits right

Many settings carry out home visits before children and families start with them.

But whether you work in a playgroup, private nursery, school nursery or Reception class, there are some important considerations to take into account before making these visits part of your practice.

If home visiting is already part of your role, take some time to reflect and review with your team.

Quick read: Five questions we need to ask about EYFS

Quick listen: What you need to know about the problems with ‘school readiness’

Want to know more? My year in teaching: adventures with my early years class

We must be clear and consistent about what we do and why we do it. There are dos and don’ts that must be regarded to make sure that a visit is successful and comfortable for all involved.

Be flexible

Remember that a visit to a family’s home is a privilege. You are their guest. In this way, the visit must take place on their terms, and at their convenience.

It can be very difficult for many parents or carers to get time off to see you during the day, and their child may be at nursery during this time, making it disruptive for everyone and hardly an ideal start.

Rather than send appointments to the families, put up a chart at your introductory sessions for new families and ask them to sign up for a convenient time.

As a teacher, I met my youngest son’s new nursery teacher at my childminder’s house during my lunch break, a mutually convenient time for us all.

Allow refusals

Remember that there is no obligation to have a visit, it is not a statutory requirement.

If a family does not want a visit for any reason this must be respected, and reasons must not be expected.

An informal meeting at a different venue may be more acceptable. I have met families in a local coffee shop, and some of my families preferred to come to school for a private cup of tea and a chat.

The core purpose of these visits must be to build up relationships founded on two-way trust and respect.

Don’t be judgemental

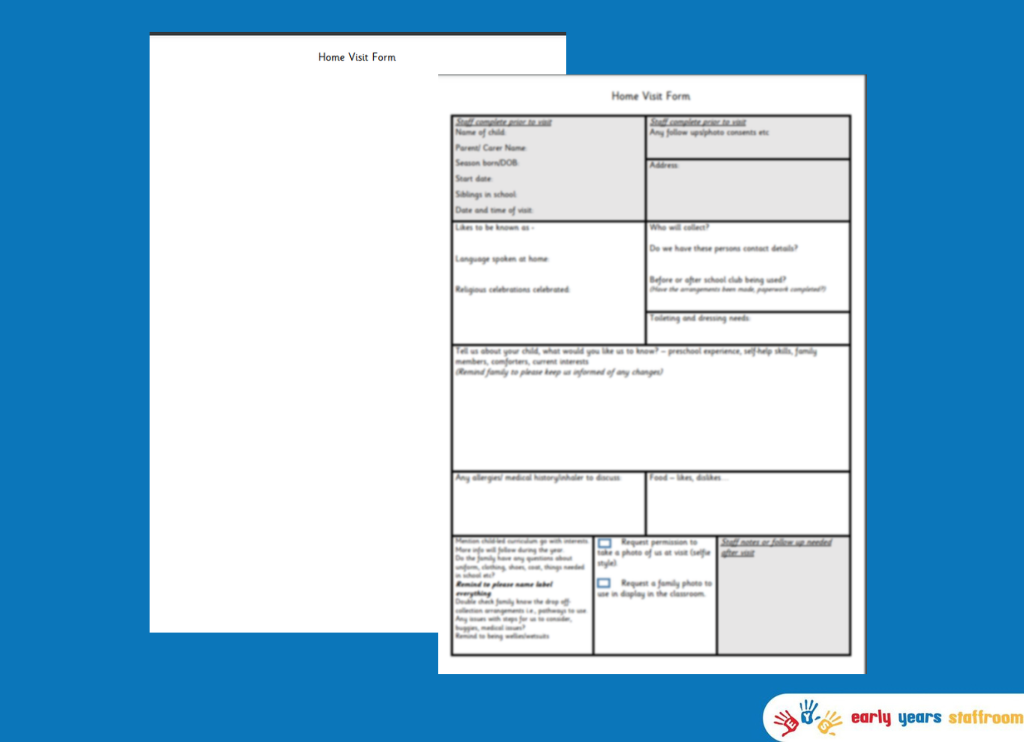

In order to build up this trust and respect, the home visit must not to be viewed as a time for form filling or cross examination.

It is not an assessment or test - remember that some families will have had other agencies involved in their lives which may not have been such a pleasant experience.

Home visits are not judgemental, and should not be perceived as such. In this way, writing any kind of notes is inappropriate; don’t go armed with a clipboard and forms to fill in as this could easily be perceived as threatening.

Your visit is an opportunity to meet each other in an informal way, play with the children and feel relaxed in each other’s company. Building up trust and respect will help families to share things in confidence if they wish.

That is not to say that forms cannot be left with the parents to be filled in after the visit. Remember that visitors with clipboards are intimidating and this will damage any relationship.

Be sensitive to timings

Think about how long each visit needs to be, and be sure that the family knows how long you will be there. It is important that these aren’t rushed, but also that the welcome is not outstayed.

The family must feel relaxed. It is fine to accept or decline a drink or something to eat just as you would when visiting a friend.

Bring resources

Take a resource from the setting to share with the child. I always take a story sack as they enable interaction with the child, the family can join in, and the same resource will be available for them when they start at the setting.

Stay relaxed

Keeping relaxed can help families to share very private information with you. For example medical matters, special needs or family circumstances.

This must be respected as confidential and any paperwork given must be treated securely at the setting; the information should only be shared with those who need to know.

A relaxed home visit is about your team too. If you know that a colleague has specific allergies, it is always a good idea to check if a family has pets when arrangements are made.

Go in pairs

Finally, home visits must always be done in pairs. This is a safeguard for all concerned, but is also very practical - with two adults visiting there will be time for play and conversation and for everyone to feel relaxed.

Dr Sue Allingham is an EYFS researcher

Want to keep reading for free?

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Disclaimer » Advertising

- HealthyChildren.org

- Previous Article

- Next Article

History and Development of Home Visiting in the United States

Social justice movements before 1950, the war on poverty and prevention of child maltreatment, expansion of home visiting in recent decades, home visiting outside the united states, poverty, child health, and home visiting, national evaluation and evidence of effectiveness, home visiting and the medical home, recommendations and position statement, community pediatricians, large health systems, managed care organizations, and accountable care organizations, researchers, the aap endorses and promotes the following general policy positions and advocacy strategies:, conclusions.

- Lead Authors

- Council on community Pediatrics Executive Committee, 2016–2017

- Council on Early Childhood Executive Committee, 2016–2017

- Committee on Child abuse and Neglect, 2016–2017

Early Childhood Home Visiting

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- CME Quiz Close Quiz

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Get Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

James H. Duffee , Alan L. Mendelsohn , Alice A. Kuo , Lori A. Legano , Marian F. Earls , COUNCIL ON COMMUNITY PEDIATRICS , COUNCIL ON EARLY CHILDHOOD , COMMITTEE ON CHILD ABUSE AND NEGLECT , Lance A. Chilton , Patricia J. Flanagan , Kimberley J. Dilley , Andrea E. Green , J. Raul Gutierrez , Virginia A. Keane , Scott D. Krugman , Julie M. Linton , Carla D. McKelvey , Jacqueline L. Nelson , Emalee G. Flaherty , Amy R. Gavril , Sheila M. Idzerda , Antoinette “Toni” Laskey , John M. Leventhal , Jill M. Sells , Elaine Donoghue , Andrew Hashikawa , Terri McFadden , Georgina Peacock , Seth Scholer , Jennifer Takagishi , Douglas Vanderbilt , Patricia G. Williams; Early Childhood Home Visiting. Pediatrics September 2017; 140 (3): e20172150. 10.1542/peds.2017-2150

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

High-quality home-visiting services for infants and young children can improve family relationships, advance school readiness, reduce child maltreatment, improve maternal-infant health outcomes, and increase family economic self-sufficiency. The American Academy of Pediatrics supports unwavering federal funding of state home-visiting initiatives, the expansion of evidence-based programs, and a robust, coordinated national evaluation designed to confirm best practices and cost-efficiency. Community home visiting is most effective as a component of a comprehensive early childhood system that actively includes and enhances a family-centered medical home.

Recent advances in program design, evaluation, and funding have stimulated widespread implementation of public health programs that use home visiting as a central service. This policy statement is an update of “The Role of Preschool Home-Visiting Programs in Improving Children’s Developmental and Health Outcomes” (2009) and summarizes salient changes, emphasizes practical recommendations for community pediatricians, and outlines important national priorities intended to improve the health and safety of children, families, and communities. 1 By promoting child development, early literacy, school readiness, informed parenting, and family self-sufficiency, home visiting presents a valuable strategy to buffer the effects of poverty and adverse early childhood experiences that influence lifelong health.

The term “home visiting” refers to an evidence-based strategy in which a professional or paraprofessional renders a service in a community or private home setting. Home visiting also refers to the variety of programs that employ home visitors as a central component of a comprehensive service plan. 2 Early childhood home-visiting programs may be focused on young children, children with special health care needs, parents of young children, or the relationship between children and parents, and they can use a 2-generational strategy to simultaneously address parental and family social and economic challenges. 3

Home-visiting programs vary widely with regard to target populations and goals. Many successful home-visiting models are directed toward mothers and infants in high-risk groups, such as adolescent mothers and single-parent families. Other models concentrate on specific populations, such as recently incarcerated adolescents, children with special needs, or immigrants. Some programs are designed to identify risk factors, such as environmental hazards and maternal mental health, but others include mentoring, coaching, and other therapeutic interventions. Many employ independently licensed health professionals, but others depend on trained paraprofessionals (including community health workers) drawn from the communities they serve. Community-based care coordination (including housing, transportation, and nutritional support) often are service components. Integration with the family-centered medical home (FCMH) has been a recent focus for program improvement and medical education. 4

Home visiting began in the United States in the 1880s as an activity of each of 3 social justice movements. Derived from the British models developed a few decades earlier, home visitors were deployed to promote universal kindergarten, improve maternal-infant health through public health nursing, and support impoverished immigrant communities as part of the philanthropic settlement house movement. From the late 19th through the early 20th century, teachers and public health nurses visited communities and families to provide in-home education and health care to urban women and children. These efforts were based on the assumptions still held that education is the most powerful strategy to lift children out of poverty and that the lifelong health of families in immigrant and poor neighborhoods is improved by addressing the social and economic aspects of health and disease. 5

From the Great Depression through World War II, funding for social initiatives decreased and philanthropic support for home visitors declined. After the relatively prosperous postwar period, renewed interest developed in antipoverty activities, including home visiting, especially in the context of the Civil Rights Movement. In the 1960s, home visiting became an important component of the government’s so-called War on Poverty. Home visiting was and remains integral to programs such as Head Start, although it is applied on a limited basis compared with Early Head Start, for which home visiting is a central service component. A decade later, many home-visiting programs shifted to include case management, intending to help families achieve self-sufficiency and link them to other broad community support services. 6 Improving school readiness, moderating poverty-related social risk determinants, reducing environmental safety hazards, and promoting population-based health remain core goals of contemporary home visiting.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, home visiting gained renewed attention as a strategy for the prevention of child abuse and neglect, promotion of child development, and improvement of parental effectiveness. C. Henry Kempe, MD, called for a home visitor for every pregnant mother and preschool-aged child in his 1978 Abraham Jacobi Memorial Award address. 7 He suggested that integral to every child’s right to comprehensive care is the assignment of a home health visitor to work with the family until each child began school. The visionary pediatrician who developed the concept of the medical home, Cal Sia, MD, reiterated Kempe’s call to action in his 1992 Jacobi Award address 8 based on his experience with Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program, which is an innovative, statewide home-visiting initiative to prevent child abuse and neglect. Another pioneer in modern home visiting, David Olds, PhD, initiated the Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) with families at risk in Elmira, New York, in 1978. 1

Before 2009, at least 22 states recognized the critical role of home visitors within statewide systems for at-risk pregnant mothers, infants, and toddlers from birth to 5 years old. States legislated funding for home-visiting programs while insisting on proof of effectiveness, fiscal accountability, and continuous quality improvement. Even during the Great Recession that followed the US financial crisis of 2007 to 2008, some state governments enacted home-visiting legislation to ensure long-term sustainability through innovative financing mechanisms and the strategic allocation of limited public resources.

In 2009, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (Public Law Number 111-5) included $2.1 billion for the expansion of Head Start and Early Head Start (including the home-visiting components of Early Head Start) to benefit young children in low-resource communities. The next year, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) (Public Law Number 111-148) designated $1.5 billion, allocated over 5 years, for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV). The Health Resources and Services Administration currently administers the MIECHV in collaboration with the Administration for Children and Families. The allocations to states, territories, and tribal entities are designed to support the implementation and evaluation of evidence-based home-visiting programs regarding specified goals and objectives. All 50 states, the District of Columbia, and 5 US territories have home-visiting programs. 9 In addition, ACA funding provides support for home-visiting initiatives to serve American Indian and Alaskan native children through the Tribal MIECHV program. 10

Nineteen home-visiting models have met the criteria of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) for evidence of effectiveness through the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) review. Supported by federal grants through the MIECHV, states receive funding to implement 1 or more evidence-based models designated eligible by the MIECHV that best meet the needs of particular at-risk communities. The program objectives must improve outcomes that are statutorily defined and must include increased family economic self-sufficiency, improved health indicators (eg, a reduction in health disparities) in target populations, and improved school readiness. After 2013, potential program outcomes were expanded to include reductions in family violence, juvenile delinquency, and child maltreatment. 11 A review of 4 common programs illustrates the range of measurable outcomes. Healthy Families America identifies family self-sufficiency as a principal objective measured by a reduction of dependence on public assistance. 12 Early Head Start and other home-visiting programs focus on the promotion of child development and positive family relationships. NFP is designed to improve prenatal health, maternal life course development, and positive parenting. 13 Parents as Teachers promotes child development and school readiness. 14

Home visiting for families with young children is an early intervention strategy in many industrialized nations outside of the United States. In several European countries, home health visiting is provided at no cost to the family, participation is voluntary, and the service is embedded in a comprehensive maternal and child health system. 3 While visiting young mothers at home, public health nurses in other countries provide many child health-promotion services that are provided by pediatricians in the United States. For instance, Denmark established home visiting in 1937 after a pilot program showed lower infant mortality rates linked with the services of home visitors. France provides universal prenatal care and home visits by midwives and nurses, who educate families about smoking, nutrition, drug use, housing, and other health-related issues.

The Early Start program in New Zealand targets families with 2 or more risk factors on an 11-point screening measure that includes parent and family functioning. Randomized controlled trials showed improvement in access to health care, lower hospitalization rates for injuries and poisonings, longer enrollment in early childhood education, and more positive and nonpunitive parenting. 15 , 16 The Dutch NFP program, VoorZorg, was found to reduce victimization and perpetration of self-reported intimate partner violence during pregnancy and 2 years after birth among low-educated, pregnant young women, 17 and there were fewer reports of child abuse. At 24 months, measurable improvements were evident in the home environments of participating families, and the children exhibited a significant reduction in internalizing symptoms. 18

Paraprofessionals (ie, trained but unlicensed lay people) are often employed as home visitors in low-resource areas of the world. In Haiti, for example, community health workers trained by Partners in Health improve the care of those with HIV, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and such waterborne illnesses as cholera. In southern Mexico and other areas in Central America, “promotoras de salud,” or community health workers, coordinate with lay midwives to care for expectant mothers in rural, isolated, and other low-resource regions. Promotoras are deployed in many regions in the United States and have been recognized by HHS for their ability to reduce barriers and improve access to culturally informed and linguistically appropriate health care. 19

More than 1 in 5 young children in the United States live in families with incomes below the federal poverty level, and more than 2 in 5 live at less than twice that level. 20 Living at or below 200% of the federal poverty level places children, 21 especially infants and toddlers, at high risk for adverse early childhood experiences that lead to lifelong detrimental effects on health, education, and vocational success. 22 Home visitors can help families attain economic self-sufficiency by linking them to community support services (such as quality preschool) while encouraging parents to enroll in training opportunities that lead to employment. Although they differ in structure, targeted populations, and intended outcomes, high-quality home-visiting programs deliver family support and child development services that provide a foundation for physical health, academic success, and economic stability in vulnerable families that are at risk for the adverse effects of poverty and other negative social determinants of health.

By applying multigenerational interventions, home visiting may improve child health and family wellbeing in many domains. Individual neuroendocrine-immune function, behavioral allostasis, and relational health are all established in the first 3 years of life, 23 when home visiting is most often applied. 24 The emerging science of toxic stress indicates that poverty and its accompanying problems, such as food insecurity, may disrupt the architecture and function of the developing brain. 25 , 26 Home visitors have the opportunity to assess risk and protective factors in families, identify potential adversity, and intervene at the earliest opportunity. By promoting supportive relationships, reducing parental stress, and increasing the likelihood of positive experiences, home visiting may help avoid the deleterious behavioral and medical health outcomes associated with child poverty. 27 , – 31

Young mothers in poverty disproportionately suffer moderate to severe symptoms of maternal depression, elevating the risk of poor developmental and educational outcomes for their children. 32 Almost 1 in 4 mothers who are near or below the federal poverty level experience significant depression, but few obtain appropriate treatment. In-home cognitive behavioral therapy is a novel treatment modality for maternal depression that has proved to be effective in early trials. 33 Combining in-home cognitive behavioral therapy with other home-visiting programs, such as Early Head Start, that promote positive parenting and infant development provides a model of 2-generational care that has the potential to mitigate the effects of poverty and improve both family financial stability and school readiness. 34

Home-visiting programs are most effective when they are components of a community-level, comprehensive early childhood system that reaches families as early as possible with needed services, accommodates children with special needs, respects the cultures of the families in the communities, and ensures continuity of care in a continuum from prenatal life to school entry. 35 , 36 An early childhood system may include safety-net resources (such as supplemental food and subsidies for housing, heating, and child care), adult education, job training, cash assistance, quality child care, early childhood education, and preventive health services. 37 Communicating the strengths and risk factors of individual families to the FCMH may further increase the coordination of care and efficient use of services. 38

When the MIECHV program was established by the ACA, HHS established the HomVEE review of the research literature on home visiting. 11 Results of that review are used to identify home-visiting service delivery models that meet HHS criteria for evidence of effectiveness because, by statute, at least 75% of the funds available from the ACA are to be used for programs that use service delivery models that are evidence based. The HomVEE conducts a yearly literature search to identify promising studies of home-visiting models. It includes only studies that are considered to meet quality standards on the basis of overall design (only randomized controlled trials or quasiexperimental studies are included) and design-specific criteria. Studies that meet criteria for entry are then assessed for outcomes in the following 8 domains, as defined by HHS:

Child health;

Maternal health;

Child development and school readiness;

Reductions in child maltreatment;

Reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime;

Positive parenting practices;

Family economic self-sufficiency; and

Linkages and referrals.

To meet HHS criteria for evidence of effectiveness, home-visiting models must demonstrate favorable outcomes in either 1 study with results in 2 or more domains or 2 studies with significant benefits in the same domain. To be included, study designs must meet evaluation quality standards, and outcomes need to show statistically significant benefits using nonoverlapping analytic samples. As of April 2017, the 18 models that meet these standards (along with 2 programs that do not meet criteria for implementation) with target populations, ages of participants, and outcomes for which there is evidence are listed in Table 1 . 11

Home-Visiting Programs Meeting HHS Criteria for Evidence of Effectiveness (as of April 2017)

Reference: https://www.mathematica-mpr.com/our-publications-and-findings/publications/home-visiting-evidence-of-effectiveness-review-executive-summary-april-2017 . Descriptions of specific home-visiting programs by state can be accessed at: https://homvee.acf.hhs.gov/models.aspx .

Outcomes: (1) child health; (2) maternal health; (3) child development and school readiness; (4) reductions in child maltreatment; (5) reductions in juvenile delinquency, family violence, and crime; (6) positive parenting practices; (7) family economic self-sufficiency; and (8) linkages and referrals.

A rapidly expanding evidence base documents the benefits of high-quality home-visiting programs, especially when they are integrated in a comprehensive early childhood system of care. 39 Home visiting has been shown to increase children’s readiness for school, promote child health (such as vaccine rates), and enhance parents’ abilities to promote their children’s overall development. There is evidence that home visiting reduces the risk of both child abuse and unintended injury. 16 , 40 Maternal health is improved by more frequent prenatal care, better birth outcomes, and early detection and treatment of depression. 41 Outcome studies have established the effectiveness of home visiting by nurses or community health workers in reducing child maltreatment, 42 improving birth outcomes, 43 and increasing school readiness. 44

A close examination of the evidence of effectiveness published in 2015 by the HomVEE review provides additional insights about the potential benefits and limitations of current models of home visiting. 11 Of the 44 models assessed in 2015, 19 showed improvements in at least 1 primary outcome measure, and 15 had favorable effects on secondary measures. These results are consistent with both the broad scope of many of the models as well as the likelihood that improvements in 1 domain sometimes lead to benefits in another (eg, positive parenting improving child development). All 19 models that showed positive results had evidence of sustained benefits for at least 1 year after enrollment.

In addition to the 19 models approved in 2015, 8 of the 25 that were not approved had evidence of benefit, perhaps because of stringent criteria for study quality and number. Even among programs showing positive outcomes, there was not a high level of consistency across domains. For example, only 7 of 19 models demonstrated benefits in the same domain across 2 or more studies. Many effect sizes were fairly small (approximately 0.2 SDs) but comparable to those seen in many studies of programs located in other settings (eg, early child education). 45 However, modest effect sizes in studies concerning developmental delay can result in important population-level effects given the high proportion of children in low-income families (nearly 20%) meeting criteria for early intervention services. 46 , 47

Longitudinal studies within the HomVEE review of the NFP have shown improvements in adolescent mental health, in middle school achievement, over substance use and/or criminality immediately after high school, as well as in overall maternal and child mortality. 48 , – 50 Other studies document the persistence of beneficial outcomes after population-level scaling. A study of Durham Connects (also known as Family Connects) showed more than 80% participation and 84% adherence among all mothers delivering in Durham, North Carolina, during an 18-month period. 51 Researchers in this study, using rigorous methodology, documented important and beneficial effects on child health, including a 59% reduction in emergency medical care, an increase in positive parenting, successful linkages to community services, and improved maternal mental health. In addition, a large-scale study of SafeCare home-based services showed reductions in reports to child protective services after a scale-up of the program in Oklahoma. 52 These beneficial outcomes of rigorous program evaluation counterbalance other studies that found little or no benefit after a scale-up, such as the finding of reduced implementation fidelity and limited benefit after scaling up Hawaii’s Healthy Start Program. 53

Other studies document the capacity of home visiting to successfully target specific high-risk populations and implement interventions of varying intensity specific to the intended outcome. For example, Computer-Assisted Motivational Intervention, when applied in combination with home visiting, successfully reduced subsequent pregnancies among pregnant teenagers. 54 Other 2-generational interventions, including Family Spirit (which targets American Indian teen-aged mothers) and Family Check-Up (which targets young mothers with depression), improved behavioral problems in infants and young children as well as the mental health of the young mothers. 55 , – 57

Finally, the outcomes documented by the HomVEE need to be considered in the context of a number of meta-analyses and systematic reviews that have been conducted other than the HomVEE. One of the most cited is a meta-analysis that documented significant benefits across 4 broad domains, including child development, child abuse prevention, childrearing, and maternal life course. 58 Benefits were maximized when specific rather than general populations were targeted, when interventions used professionals versus paraprofessionals, and when interventions were more specifically focused on parental rather than child wellbeing. 59 , – 61

Integration of home visiting with the medical home expands the multidisciplinary team into the community, enhancing the goals of communication, coordination of care, and comprehensive care. With effective leadership, the pediatric or FCMH may become a community hub that connects early education and child development activities with health promotion to support maximum outcomes for children and families. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement has described the triple aim as improvement of the health of populations, improvement of the quality of care and experience of each patient, and the reduction of per capita cost. The history of home visiting also reveals another triple aim of improving health, preparing children for education, and reducing poverty. An advanced medical home that reaches out to the community by collaborating with or integrating a high-quality home-visiting program has the potential of meeting both sets of triple aims. 62 , 63

Some important factors that are common among home-visiting programs that are also characteristic of an FCMH include an emphasis on relationships, the provision of culturally informed care, coordination with other community support agencies, an emphasis on strength-based assessments, and collaboration with families to support self-identified goals. Of particular importance is the relationship that develops between the visitor and the family engaging in a natural environment and the consequent improvement in the relationships among family members. 64 As more has been learned about toxic stress and its negative effect on the life trajectory, close and nurturing relationships have emerged as a most important protective factor. The home visitor can extend the support of the medical home into the community and provide an important link for the family to the relationship with a compassionate pediatric practitioner while improving family relational health. 65

The integration or colocation of home visiting with the medical home presents many opportunities for synergy and collaboration. The joint statement from the Academic Pediatric Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) regarding integration of the FCMH with home visiting emphasizes the potential for coordinated anticipatory guidance, improved early detection, and enhanced community involvement. 66 Recommendations in the joint statement include integrated, computerized record systems; the creation of a joint registry; coverage of home visiting by payers, including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program; and supporting the evaluation of coordination between an FCMH and home visiting. In a collaborative model, referrals between a pediatric practitioner and the home visitor may constitute a warm handoff (face-to-face introduction), increasing the likelihood that family concerns are communicated and addressed. For example, a home visitor has the opportunity to complete developmental screening with the parent in a child’s natural environment. The results of screening may be communicated to the pediatric practitioner for use and comparison with the developmental assessment during health-promotion visits. A shared chronic condition care plan facilitates common therapeutic goals, linkages to community resources, and follow-up on referrals. Particularly helpful have been home-visiting strategies for children with diabetes or asthma. Researchers have associated home visiting with improvements in symptoms, urgent care use, and family quality of life. 67

Home visiting may be used effectively as an adjunctive strategy in comprehensive community-based programs serving children. Although not approved for MIECHV funding, Healthy Steps for Young Children is a comprehensive primary-care model that may include on the treatment team a home visitor who supports positive parenting, provides in-home developmental assessment, and links the family more strongly to the medical home. 68 The example of Healthy Steps illustrates the significant potential benefits from improved collaboration between the medical home and community home-visiting programs. These include common documentation, centralized intake services, strength-based assessments, colocation of home visitors in the pediatric practice, and multidisciplinary team meetings convened by the practice. Through these coordinated activities, home visitors are in partnership with the medical home to build parental resilience, promote child development, and support healthy family relationships. 66 , 69 Other models that similarly employ home visiting as an adjunctive strategy, such as the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Bridging the Word Gap Research Network 70 , 71 and the New York City Council’s City’s First Readers program, exemplify systematic linkages among the medical home, home-visiting programs, and other community-based services with early childhood education. 63 , 72

Because home-visiting models and programs cross many health systems and involve many funding sources, this policy divides recommendations into the following 3 levels: community pediatricians, large health systems, and researchers. The section concludes with AAP-supported federal and state advocacy strategies.

Provide community-based leadership to promote home-visiting services to at-risk young mothers, children, and families;

Be familiar with state and local home-visiting programs and develop the capacity to identify and refer eligible children and pregnant mothers;

Consider opportunities to integrate or colocate home visitors in the FCMH;

Recognize home-visiting programs as an evidence-based method to enhance school readiness and reduce child maltreatment;

Recognize home visiting as a promising strategy to buffer the effects of stress related to the social determinants of health, including poverty; and

Serve as a referral source to home-visiting programs as a strategy to engage families in services and strengthen the connection between home visiting and the medical home.

Develop a continuum of early childhood programs that intersects or integrates with the FCMH;

Ensure that home-visiting programs are culturally responsive, linguistically appropriate, and family centered, emphasizing collaboration and shared decision-making;

Ensure that all home-visiting programs incorporate evidence-based strategies and achieve program fidelity to ensure effectiveness;

Support the use of trained community health workers, especially in lower-resourced, tribal, and immigrant communities; and

Develop training and certification programs for community health workers to ensure quality and fidelity to program expectations.

Improve understanding of how to engage difficult-to-reach and high-risk communities and populations, including immigrant families, families with low literacy and/or health literacy and limited English proficiency, families that are socially isolated, and families living in poverty in evidence-based home-visiting programs;

Improve understanding of how to take successful programs to scale while maintaining fidelity;

Improve understanding of how to optimize links between evidence-based home-visiting programs and the medical home;

Determine the degree to which the medical home and strategies using multidisciplinary and integrated interventions can provide added value to and synergy with evidence-based home-visiting programs;

Determine the degree to which home-visiting programs can augment the medical home in the prevention or mitigation of chronic disease, such as asthma and obesity, and associated morbidities;

Improve understanding of how to tailor the implementation of evidence-based home-visiting programs to diverse populations with heterogeneous strengths and challenges; and

Investigate and establish the cost-effectiveness and return on investment of home-visiting programs as well as program components.

The continuation and expansion of federal funding for evidence-based home-visiting programs;

Public support for the dissemination of home-visiting programs that meet the HomVEE criteria for evidence of effectiveness as well as other programs with early and promising evidence of potential effectiveness;

The establishment of state systems that integrate home-visiting infrastructure (such as data collection and evaluation) into a comprehensive early childhood service system;

Coordination across state agencies and health systems that serve young children to build an efficient and effective infrastructure for home-visiting programs;

The simplification and standardization of referral processes in and among states to improve the coordination of care and integration of home-visiting services with the medical home; and

The inclusion of home-visiting experience in community pediatrics education and exposure by residents and medical students to the evidence of effectiveness of home-visiting models.

The objectives of contemporary home-visiting programs have strong roots in public health, early childhood education, and antipoverty efforts. Home visiting has expanded rapidly in the recent past, with the current generation of programs providing strong evidence of effectiveness in many domains of family life. Rigorous national outcome evaluations substantiate that home-visiting programs are effective in the promotion of healthy family relationships, improvement of overall child development, prevention of child maltreatment, advancement of school readiness, and improvement of maternal physical and mental health. By linking families to opportunities such as employment and continuing education, home visiting increases family economic stability and thereby is a successful antipoverty strategy. Home-visiting programs have shown the most effectiveness when they are components of community-wide, early childhood service systems. With pediatrician leadership, the FCMH can serve as the hub for coordinating community-based, family support programs at the intersection of early education with public health promotion designed to help children avoid the lifelong effects of early childhood adversity.

American Academy of Pediatrcs

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

family-centered medical home

US Department of Health and Human Services

Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness

Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program

Nurse-Family Partnership

Dr Duffee was intimately involved with the concept, organization, and design during the early phases of writing, he reviewed the contributions of the other authors, consolidated the contributions (along with his own) into the final product, took responsibility for responding to comments and direction from staff and the Board of Directors, and reviewed the references in detail to ensure that the evidence supports the recommendations; and Drs Kuo, Legano, Mendelsohn, and Earls assisted with revisions; and all authors approve the final manuscript as submitted.

This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have filed conflict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any conflicts have been resolved through a process approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication.

Policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the organizations or government agencies that they represent.

The guidance in this statement does not indicate an exclusive course of treatment or serve as a standard of medical care. Variations, taking into account individual circumstances, may be appropriate.

All policy statements from the American Academy of Pediatrics automatically expire 5 years after publication unless reaffirmed, revised, or retired at or before that time.

FUNDING: No external funding.

L ead A uthors

James H. Duffee, MD, MPH, FAAP

Alan L. Mendelsohn, MD, FAAP

Alice A. Kuo, MD, PhD, FAAP

Lori Legano, MD, FAAP

Marian F. Earls, MD, MTS, FAAP

Council on c ommunity Pediatrics Executive Committee , 2016–2017

Lance A. Chilton, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Patricia J. Flanagan MD, FAAP, Vice Chairperson

Kimberley J. Dilley, MD, MPH, FAAP

Andrea E. Green, MD, FAAP

J. Raul Gutierrez, MD, MPH, FAAP

Virginia A. Keane, MD, FAAP

Scott D. Krugman, MD, MS, FAAP

Julie M. Linton, MD, FAAP

Carla D. McKelvey, MD, MPH, FAAP

Jacqueline L. Nelson, MD, FAAP

Jacqueline R. Dougé, MD, MPH, FAAP – Chairperson, Public Health Special Interest Group

Kathleen Rooney-Otero, MD, MPH – Section on Pediatric Trainees

Camille Watson, MS

Council on Early Childhood Executive Committee , 2016– 20 17

Jill M. Sells, MD, FAAP, Chairperson

Elaine Donoghue, MD, FAAP

Marian Earls, MD, FAAP

Andrew Hashikawa, MD, FAAP

Terri McFadden, MD, FAAP

Alan Mendelsohn, MD, FAAP

Georgina Peacock, MD, FAAP

Seth Scholer, MD, FAAP

Jennifer Takagishi, MD, FAAP

Douglas Vanderbilt, MD, FAAP

Patricia Gail Williams, MD, FAAP

Laurel Murphy Hoffmann, MD – Section on Pediatric Trainees

Barbara Sargent, PNP – National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners

Alecia Stephenson – National Association for the Education of Young Children

Dina Lieser, MD, FAAP – Maternal and Child Health Bureau

David Willis, MD, FAAP – Maternal and Child Health Bureau

Rebecca Parlakian, MA – Zero to Three

Lynette Fraga, PhD – Child Care Aware

Charlotte Zia, MPH, CHES

Committee on Child a buse and Neglect , 2016–2017

Emalee G. Flaherty, MD, FAAP

Amy R Gavril, MD, FAAP

Sheila M. Idzerda, MD, FAAP

Antoinette “Toni” Laskey, MD, MPH, MBA, FAAP

Lori A. Legano, MD, FAAP

John M. Leventhal, MD, FAAP

Harriet MacMillan, MD – American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

Elaine Stedt, MSW – Department of Health and Human Services Office on Child Abuse and Neglect

Beverly Fortson, PhD – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Tammy Hurley

Competing Interests

Advertising Disclaimer »

Citing articles via

Email alerts.

Affiliations

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Policies

- Journal Blogs

- Pediatrics On Call

- Online ISSN 1098-4275

- Print ISSN 0031-4005

- Pediatrics Open Science

- Hospital Pediatrics

- Pediatrics in Review

- AAP Grand Rounds

- Latest News

- Pediatric Care Online

- Red Book Online

- Pediatric Patient Education

- AAP Toolkits

- AAP Pediatric Coding Newsletter

First 1,000 Days Knowledge Center

Institutions/librarians, group practices, licensing/permissions, integrations, advertising.

- Privacy Statement | Accessibility Statement | Terms of Use | Support Center | Contact Us

- © Copyright American Academy of Pediatrics

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Early Years Consultant - Cathy Renwood

EYFS Guide -The Importance of Home Visits

Transition into the eyfs.

As the start of the new school year approaches Reception teachers will be getting ready to welcome and settle in their new class. This is such an important time as the transition into Reception should be a positive and exciting beginning for children on the start of their school and learning journey.

Home visits play an important part in ensuring this new transition is a smooth and supportive time for children. Home visits are not statutory however they do reflect good EYFS practice and provide an important initial link for positive parental interactions.

Continuity of experience

Children often act differently in their home environment and this gives teachers a good insight into the child and an understanding of their interests and development. It also enables children to have a chance to get to know their teacher on a one to one basis and begin to establish a relationship. This can help to reduce anxiety about starting school and also the child will have a familiar face on their first day.

Parental Involvement in the EYFS

The visits also provide Parents with an opportunity to speak about any particular needs their chid may have. A lot of Parents aren’t comfortable to do this in a big welcome meeting or when they first meet the new teacher in a school environment. Home visits act as a way of opening up lines of communication between home and school.

Home visits also provide the ideal opportunity for discussing with Parents the schools transition procedures and arrangements. Lunch, play times and support systems that need to be put into place can be talked about.

Developing Home/School Links in the EYFS

Home visits and developing those vital links of communication with the home and establishing relationships with children and family members ensure the transition to school is a happy one. Smooth transition enables a positive start to the school year for children, Parents and teachers alike. The sooner children are settled and relaxed in their learning environment their love and zest for learning will begin and develop.

If you have any concerns about transition or need help to develop your EYFS provision please get in touch.

For inquiries please call

07807 942119, [email protected], share this:.

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- K-12 Education

- Higher Education

- Early Education

- Early Intervention

- News & Resources

3 Strategies to Help States and Regional Programs Improve Home Visits for Families

Sitting at a tiny table, sippy cup in hand, two-year-old Julio giggles as his speech therapist reads The Very Hungry Caterpillar for the third time. Julio’s mother sits with them at the table. Between pages, she proudly shares how her son increasingly points to and names his favorite foods during mealtime — a skill that Julio has worked hard to improve during home visits with his speech therapist. As if on cue, Julio points to the refrigerator and demands, “Juice!” clearly and without hesitation.

This uplifting scene is a familiar one to the thousands of home visit staff who provide essential early intervention (EI) services to families across the United States. Home visits are a critical component of quality support for young children navigating developmental delays or disabilities. Families learn approaches to use to promote their child’s early development through naturally occurring learning opportunities. This practice not only creates positive outcomes for children but also benefits the entire family unit and the broader community — the ultimate goal of any EI service.

Yet many families still face the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, including exacerbated racial education and health inequities, longer wait times to receive evaluations and establish eligibility, and a reduction in the quality and frequency of services. This all can make getting the support their children need to thrive more challenging. In turn, EI providers have seen sharp decreases in family enrollments since 2020 ( Mersky et al, 2022 ), meaning families that may benefit from services aren’t getting them. Now more than ever, families and EI providers alike need high-quality, high-impact home visit programs.

However, local agencies and programs cannot achieve this vision alone. To ensure that every family who needs them actually receives these valuable services, these organizations need statewide and regional support. States and regional organizations have immense potential to unlock the power of home visits to meet critical family needs.

Home Visiting Today: Benefits and Challenges

Home visits have been part of EI provider practices for decades, and research repeatedly shows the many benefits of home visiting programs. A 2013 meta-analysis of research on home visitations found that these services resulted in significant improvements to the development and health of young children ( Peacock et al, 2013 ). Some individual family outcomes cited in the analysis included:

- Early prevention of risk factors and child abuse, in some cases

- Improved cognition

- Reduced problem behaviors

- Reduced instances of low birth weights and health problems in older children

Further, according to the Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness (HomVEE) project, there are 18 home visitation models that have been vetted as “evidence-based.” Empirical studies revealed that 10 of these 18 models resulted in significantly positive impacts on child development, maternal well-being, and other family outcomes. Though each model differs in its approach to family and child support, the collective outcomes from these models highlight how powerful home visiting can be.

However, programs face a number of challenges as they seek to reap the potential benefits of implementing home visits with their families. In their 2019 health policy brief , Health Affairs summarized three primary challenges that affect EI programs.

Many visitation programs are voluntary, which means that agencies must dedicate resources toward building and maintaining family enrollment on top of managing other program needs. This can be burdensome for local agencies, who may have limited staff time or funding for recruitment efforts.

Relatedly, although federal funding for the Maternal, Infant, and Early Childhood Home Visiting (MIECHV) Program was reauthorized by Congress in 2022, EI providers still by and large do not have sufficient resources to meet the broader need to support families through home visits. EI funding challenges impact more than the types and variety of services that families can receive. Funding also affects a program’s ability to recruit home visit staff and provide high-quality training to them.

Variability

Last, and most critically, there is tremendous variation among home visiting programs both in terms of implementation and efficacy. Even among those 18 models validated by HomVEE, it’s difficult to isolate which factors across these models make them so effective. This ambiguity complicates current and future efforts to expand models in new ways or recreate them in new places.

The result of these challenges is that many families and young children don’t receive the services that may allow them to best thrive. To put the opportunity into perspective, as recently as 2021, only 1.6% of all families that may benefit from home visits actually received them ( National Home Visiting Resource Center, 2022 ).

But here’s the good news: State and regional programs have a huge opportunity to mitigate these challenges , unlock the benefits of home visiting programs, and create opportunities to strengthen learning and coaching.

State & Regional Programs: Game Changers for EI Providers and the Families They Support

A statewide or regional EI program can catalyze a local agency’s impact on their families through home visits in several key ways.

First, with greater reach comes great distribution. State or regional programs are better positioned to distribute available funding strategically across local partners, prioritizing high-need programs or services. With state funding and legislature for home visitation programs on the rise ( National Conference of State Legislatures, 2022 ), there is more opportunity to both increase and allocate resources to support families that need it most.

Second, states can leverage their macro-position to catalyze communication efforts about local EI services, raising awareness among families to drive enrollment. A state or region-wide campaign can also clarify misconceptions about available programs that offer home visiting, many of which are available for free or are covered by some insurance providers.

Last, regional programs enable EI service providers to better support their families by disseminating must-have information, such as emerging trends in research or changes in legislature that may affect programs. This outreach can also arm local programs with best practices beyond home visit services themselves, such as program evaluation, continuous improvement, and data review processes. As an example, in 2018, the Center for Disease Control (CDC) partnered with four states to help spread new, critical information about autism to early childhood providers through their campaign called “Learn the Signs, Act Early.” Over 1,000 providers received statewide training on the Autism Case Training curriculum — far more than in-house or local agencies have the capacity to support on their own.

It’s clear that statewide and regional efforts to support EI funding and services work — so what can these programs do today to impact home visits tomorrow?

3 Ways States Can Catalyze Home Visiting Programs

State and regional programs are key to catalyzing the reach and impact of home visitation programs on families. From their deep experience supporting statewide early intervention and care programs, the TORSH team put together three strategies to help these critical entities unlock the power of home visits.

#1: Expand Outreach to Eligible Families of All Backgrounds

EI services are crucial tools to promote health equity among children and their families. In particular, The Education Trust highlights a critical need for states to engage BIPOC families and families who speak home languages other than English in their efforts to promote EI.

Why? Patterns of inequity in both access to and utilization of EI resources are present among these families. Research shows that Black children with developmental delays are 78% less likely to receive EI services ( Feinberg et al, 2011 ), and similar patterns of inequity emerge among children from other racial or ethnic groups other than White children ( Magnusson et al, 2016 ). The urgency to create equitable access to all families for EI support cannot be understated.

And who knows their community’s cultural diversity and backgrounds better than the local agencies that serve them? Through partnerships with local programs, states can help further spread information about these services to families of diverse backgrounds, especially those that traditionally underutilize statewide or regional intervention supports.

Here’s just one way in which states can create more equitable access to EI services. A key barrier to families accessing early intervention services is how complex and uncoordinated services often are. Minnesota, Oregon, Colorado, and many other states have invested in community-informed family navigation models that are designed to simplify the process of finding services. These models leverage local organizations and agencies to connect families with a person in their community who shares their language and race/ethnicity, acting as guides for the process. These guides work closely with families to determine what services they’re eligible for and then help them take the steps necessary to receive services. Support can include explaining the process, helping to fill out forms, and following up by phone, text, email, and even home visits to ensure families are receiving the services they need.

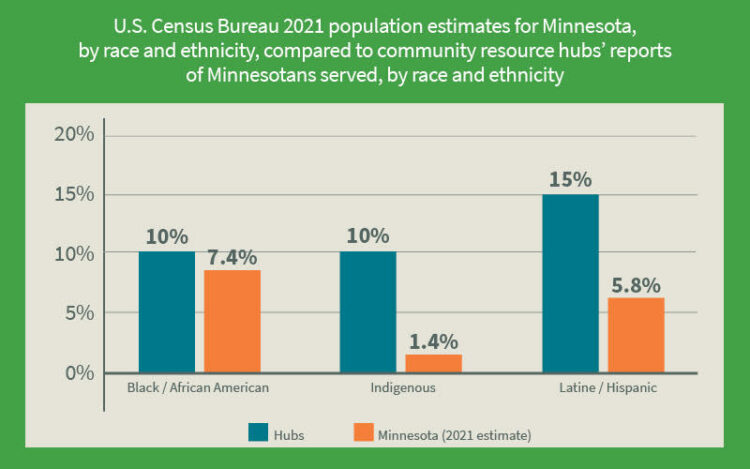

The results of these statewide efforts are powerful. In Minnesota , the community resource hubs served a greater percentage of people from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds than their populations in the state. Here’s a snapshot, 15% of the people served were Latino (of any race), 10% were Black, and 10% were Indigenous. For context, the state’s population of Latino people is just 5.8%,the population of Black people is only 7.4%, and Indigenous people account for only 1.4% of the population. This locally-based model is hugely successful in reaching historically underserved communities in the state and is inspirational for other organizations to create more equitable access to EI services for all families.

#2: Invest in Professional Development for Staff

Whether they’re conducting assessments, coaching parents, or providing other services, home-visiting staff are the bridge between what families may need and the services that can help. However, delivering high-quality services during home visits means providing practitioners with more than a one-time workshop or training series. States are well positioned to ensure home visit providers receive ongoing professional learning and coaching — not only about evidence-based practices for EI but also about programmatic processes for continuous improvement.

Several state and regional programs offer inspiration with their comprehensive professional development approach for EI providers. For example, Florida’s Early Steps program utilizes TORSH Talent , a HIPAA secure coaching and professional learning platform, to support comprehensive training for providers and caregivers in the Anita Zucker Center for Excellence in Early Childhood Studies at the University of Florida. Using TORSH Talent’s tools, experts provide evidence-based feedback on using the most current social-emotional practices and EI frameworks through video observations and coaching. These practices offer new benchmarks for creative professional learning and early intervention training that can be adopted by other service providers throughout the state.

Over in Kentucky, the University of Louisville also takes advantage of TORSH Talent to deepen their interventionists’ experience partnering with families during home visits. Ongoing mentorship and feedback are essential to the Coaching in Early Intervention Training and Mentorship Program, and TORSH Talent provides the perfect space to facilitate both. Video recordings of early intervention services, time-stamped feedback, and various rubric tools all support this effective early intervention coaching model.

The nonprofit Zero to Three shares that states can also nurture effective professional development practices by:

- Forming state or region-wide professional learning communities for home visit staff to share resources, questions, and mutual support for one another’s work

- Designing and sharing example processes or tools that support program evaluation and continuous improvement efforts, including guidance on how to leverage early intervention data to guide coaching

- Collecting and reviewing broader data trends across EI programs to inform improvements to professional development models

Professional development for early intervention service providers is a key ingredient in any effort to improve family outcomes. By investing EI funding diligently and comprehensively into professional learning for home visiting programs, states and regional entities set up local providers and families for long-term success.

#3: Leverage Technology to Increase Access to Families

From supporting virtual home visits to bolstering family-provider collaborations between live visits, technology helps broaden and deepen the impact of EI services for families. State and regional entities can provide funding for implementing digital tools like TORSH Talent to ensure all families can more easily access local services.

A beautiful example of the power that technology offers can again be found in Florida. The Autism Institute collaborated with TORSH to implement TORSH Talent as a way to support families in identifying early signs of autism in children. Using TORSH Talent, parents can video their child and securely send the videos to the Institute, whose team then reviews these videos to aid in diagnosing children with autism. If children do have autism, the Institute can provide intervention services remotely. By using TORSH Talent to provide virtual home support the Autism Institute meets their families right where they are.

“Before TORSH Talent, our impact was limited to Florida families or those with the means to travel to our center. With TORSH Talent, we’re able to offer services to any family anywhere. Our diagnosticians are now conducting virtual home observations of children with early signs of autism. Our interventionists remotely coach parents on evidence-based strategies they can use to support their child’s learning in everyday activities. One of the most exciting opportunities TORSH Talent has afforded us is the ability to train interventionists from around the world on our parent-implemented Early Social Interaction model. TORSH Talent removes barriers to our goal of making early detection and early intervention viable for all families regardless of location or socioeconomic status.”

Integrate Evidence-Informed Practices in Home Visiting Programs with TORSH

The Communication and Early Childhood Research and Practice Center (CEC-RAP) is dedicated to advancing the field of early intervention and education for young children with disabilities, communication disorders, and/or multiple risks. Their interdisciplinary approach fosters collaboration with projects nationwide, allowing for groundbreaking research and service delivery expansion.

By partnering with TORSH, CEC-RAP empowers early intervention providers with professional development and coaching from a distance. Regardless of which state they’re located in, early intervention providers can effortlessly share their practice videos with agency team members and external coaches from Florida State University, where CEC-RAP is based. This seamless collaboration, powered by TORSH Talent , ensures optimal support and better outcomes for children and their families.

TORSH Talent also gives practitioners access to a best practices library and comprehensive self-assessment capabilities conveniently located in one platform. Early intervention providers are empowered to be internal coaches, promoting sustainability in their states by embedding Family Guided Routines Based Intervention (FGRBI) into their home visiting practices.

From building a comprehensive training resource library to driving high-impact virtual coaching, statewide and regional programs can take full advantage of the easy-to-use and secure tools built into TORSH Talent, including tools for:

- Video-based observation

- Providing targeted, specific feedback to early interventionists on their interactions with children and families

- Synchronous and asynchronous collaboration

- Individualized coaching and mentoring

- Insights to guide professional learning and training

Discover how state and regional early intervention programs can leverage TORSH Talent to increase family engagement, strengthen home visit programs, and pave the way to a better future for all families and young children. Contact us now to get started supporting deeper learning, greater collaboration, and a stronger practice.

5 Tips to Help Teachers Overcome Video Anxiety

Massachusetts Adopts Torsh TALENT

Instructional Coaching: Classroom Management Through Data-Driven Strategies for Teachers

Thanks for subscribing to our blog! You should receive a confirmation e-mail soon.

Resource Toolkit for Home Visiting and other Early Childhood Professionals

Below you will find a variety of topics which you can explore. Our goal is provide current research and resources to support you in your role of supporting infants, toddlers, young children and their families and caregivers. Each will link you to resources related to that topic; articles, webinars, websites, books and face to face training opportunities. If you have resources that you would like us to post and share with other home visiting and family support professionals, please send those to [email protected]

One of the things different experts are talking about it how this whole Covid-19 is impacting our emotional health. Check out this interesting article to understand the role of grief and the stages of grief in this experience and how it provides another lens and way to look at things during this difficult time. https://hbr.org/2020/03/that-discomfort-youre-feeling-is-grief

The Ounce has launched a new knowledge-sharing platform for the early childhood community. Connect with organizations, community leaders, and experts online to help support children, families, and each other: https://ecconnector.org

Website for home visiting professionals related to best practices and information for services during this time

- https://institutefsp.org/covid-19-rapid-response

- Office of Children’s Mental Health resources page and also have attached their newest newsletter https://children.wi.gov/Pages/Mental-Wellness-During-COVID-19.aspx

Well Badger has COVID-19 curated list of resources for families. Specialists are available to handle COVID-19 related questions and referrals. Services are available to individuals in Wisconsin operating Monday through Friday from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Specialists are available via email, text message, online live chat and online searchable database.

- Tips for Families: Coronavirus

- Talking to Kids about the Coronavirus

- Tips on Doing Virtual Visits

- Tips on Mental Health and Self-Care

- Health and Human Services guidance on Telehealth

- Virtual Visit Readiness – learn the basics of different types of technology to connect with families.

- Have you checked out the new Wisconsin DHS website for information and updates on all things COVID-19? https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/covid-19/prepare.htm This website is updated regularly with the latest information.

- Self-care during these times is critical for keeping it all together. Our partner WI-AIMH has collected and posted a bunch of resources on their website in the Covid section. Some are in our toolkit and there are more worth checking out here

Webinars & Podcasts

Reflective Supervision / Consultation Webinars Available

In partnership, the Alliance for the Advancement of Infant Mental Health® and First3Years are excited to provide Reflective Supervision/Consultation training through on-demand webinars.

Webinar content consists of three 1-hr meaningful modules and best practice guidelines for Reflective Supervision/Consultation.

· Session 1: Reflective Supervision/Consultation: How Do I Begin?

· Session 2: Reflective Supervision/Consultation: Best Practices

· Session 3: Reflective Supervision/Consultation: Parallel Processing

For additional information visit:

https://first3yearstx.org/reflective-supervision-consultation-w ebinars/

COMING SOON:

Six Weeks of FREE Online Professional Development

Starting June 1,

NAEYC will offer over 100 presentations of content shared by NAEYC experts and a diverse group of presenters from all sectors of the industry. Our presenters include policy experts, higher education faculty, school leaders, researchers, and educators.

While typically this type of content is only offered at NAEYC Professional Learning Institute , we are providing access to these presentations during the NAEYC Virtual Institute at no charge as our gift to you for all that you give to young children and their families.

Who can participate?

The NAEYC Virtual Institute is open to everyone; early childhood professionals, advocates, families and supporters who are interested in early childhood education. You do not need to be a NAEYC member to participate.

What is included?

Explore over a hundred presentations, covering diverse topics from presenters who would have presented at the Professional Learning Institute. Attendees will receive a certificate of attendance for each presentation they view.

How do I participate?

Each week you’ll have the opportunity to login and select from a variety of new presentations to meet your needs.

Stay tuned for more information on how to sign up!

Another resource and opportunity for your well-being during this time is a new partnership to present a series of three webinars on mindful self-compassion (Please see below)

The Maritz Family Foundation is supporting a series of three webinars beginning April 29 , presented by the Brazelton Touchpoints Center, the University of Washington Center for Child and Family Well-Being, and the Center for Mindful Self-Compassion. These webinars will feature leaders in the field sharing appropriate and timely information and practices relevant to the current global crisis and beyond.

During these times when individual, family, and system stress is so amplified, we are particularly vulnerable to trauma, burnout, and deep fatigue. The always important emotion regulation and stress management skills, along with compassion practices, are essential for our ability to navigate these stormy seas. Each webinar will offer an opportunity to explore these skills and practices and consider the many ways they can support us.

We would greatly appreciate your sharing this information with your network(s) via email, newsletter, and/or social media, whichever is best and easiest for you. And please let me know if you have any questions or comments.

Here is a direct link for information and registration:

https://www.brazeltontouchpoints.org/mindful/

- Wi-AIMH has also collected some resources to share with and to support families around Covid which can be found here. These include resources on how to talk with children and strategies for creating routines and other concrete tools.

- In response to the COVID 19 Pandemic, Rogers InHealth staff have translated the strategies from Compassion Resilience into the context of this pandemic. As we share the resources out with people across our nation, we want to be sure you have access to the link for yourself, your co-workers and your loved ones. There are nine unique blogs and six unique videos “Staying Resilient During COVID -19”They can be found at this link – https://compassionresiliencetoolkit.org/staying-resilient-during-covid-19/ The blogs and videos can also be accessed from a banner link at www.wisewisconsin.org or www.compassionresiliencetoolkit.org

- Link quickly to the National Alliance for Home Visiting Models COVID information through https://www.nationalalliancehvmodels.org/rapid-response

- “Promoting Effective Parenting with Motivational Interviewing.”

- Did you miss the webinar last week with Dr Bruce Perry – or were you not able to get into the meeting? Here is the recorded session Coping with COVID19: Helping Children and Families Manage Stress and Build Resilience

- Series of Podcasts from Nationally Renown Brene Brown can be found here with many topics that hit the mark with current experiences. Check out her new series here

Abuse/Neglect and Adverse Childhood Experiences

- What is Considered Child Abuse? Psychology Today article covers the legal meaning of the term child abuse and links to states’ reporting laws and commonly asked questions about mandated reporting.

- InBrief: The Science of Neglect This short video, from the Center on the Developing Child, Harvard University, reveals the four types of unresponsive care and the impact of neglect on a young child’s brain development. Look for other resources related to neglect on this website.

- The CDC website has the original ACE study, resources, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System ACE data, journal articles and presentation graphics.

- The Child Abuse and Prevention Board has Information related to the original ACE study and ACEs data specific to Wisconsin, including a Wisconsin ACE brief and other reports related to our state.

- Services for Families of Infants and Toddlers Experiencing Trauma: A Research-to-Practice Brief . Beginning life in the context of trauma places infants and toddlers on a compromised developmental path. This brief summarizes what is known about the impact of trauma on infants and toddlers, and the intervention strategies that could potentially protect them from the adverse consequences of traumatic experiences. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation.

- How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime Nadine Burke Harris Ted Talk.

- Take The ACE Quiz — And Learn What It Does And Doesn’t Mean , NPR

Online Learning

- Childhood Adversity Narratives (CAN) Developed by 5 researchers from around the country, this webinar is meant to help inform policy makers and the public about the costs and consequences of child maltreatment and adversity. Feel free to use their work, and provide appropriate citations, to educate others.

- Marks that Matter, Sentinel Injuries, and Other Opportunities for Child Abuse Prevention is a 25-minute module that will teach you about marks that matter and sentinel injuries, including why they are significant, who is at risk, and what to do if you suspect abuse. It is intended for childcare workers, child welfare workers, family support staff, and home visitors, but any person working with children will find it a useful tool. This module can be viewed on your computer or mobile device.

- WI Mandated Reporter Online Training Reporting requirements vary slightly for a few groups. Learners can select the affiliation that best fits their role in the WI Child Welfare Professional Development System online training.

- Coping with Early Adversity and Mitigating its Effects—Core Story: Resilience From the Center for Advanced Studies in Child Welfare, this 7 min. video addresses effective ways to help children cope and build resilience through adversity.

- NEAR@Home is a training manual with guided processes to help home visitors learn and practice language and strategies to safely and effectively talk about childhood trauma and the ACEs questionnaire in a safe, respectful, and effective way for both home visitor and family.

- Tip Sheet CES

- Childhood Experiences Survey Developed through UW Milwaukee for home visitors, this validated tool expands the framework of the original ACEs survey to include additional questions around poverty, bullying, absence of a parent, and death of a close family member.

Prevention Advocacy

- Child Welfare League of America with the following text,. CWLA leads and engages its network of public and private agencies and partners to advance policies, best practices and collaborative strategies that result in better outcomes for children, youth and families that are vulnerable.

- Prevent Child Abuse America PCA’s mission is to prevent the abuse and neglect of our nation’s children. Their website offers an activity toolkit, stats and figures, tip sheets for parents, research and ways you can make a difference.

- Wisconsin Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Board The Wisconsin Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention Board is committed to mobilizing research and practices that prevent the occurrence of child maltreatment. Learn about abuse and neglect risk factors and protective factors, as well as frameworks for child maltreatment prevention.

- Safe Haven for Newborns Information Safe Haven, also known as “infant relinquishment”, this law allows a parent to leave their newborn in a safe place in certain circumstances with certain individuals. Learn more about this WI law, the Maternal and Child Health Hotline and crisis support on this webpage.

- Wisconsin Sex Trafficking and Exploitation Indicator and Response Guide for Mandated Reporters ( English ) ( Spanish )

- Awareness to Action (A2A) A2A is an initiative focused on preventing child sexual abuse by helping adults and communities take action to protect children through awareness, education, prevention, advocacy and action, through the Child Abuse Prevention Board, Children’s Hospital of WI.

Tip Sheets/ Guides

- Tip Sheet: Talking to Children and Teens about Child Abuse Children need accurate, age-appropriate information about child sexual abuse and confidence that adults they know will support them. This tip sheet can help!

- Books to Help Parents Talk About and Respond to Child Sexual Abuse The Committee for Children features a list of books which provide valuable information for parents to keep their kids safe.

- Long-term consequences of Child Abuse and Neglect fact sheets.

- Babies Cry, Be Prepared Free downloadable brochure in English, Spanish and Hmong from Child Abuse and Prevention Board.

- Signs of Child Abuse and Neglect The WI Dept of Children and Families has outlined the signs of neglect and physical, sexual, and emotional child abuse, to help readers be prepared to recognize situations that may need to be reported.

Text Resources

- Services for Families of Infants and Toddlers Experiencing Trauma: A Research-to-Practice Brief , Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation