Why Do Our Minds Wander?

A scientist says mind-wandering or daydreaming help prepare us for the future

Tim Vernimmen, Knowable Magazine

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a5/8b/a58b6ad5-aabb-49b6-9565-941c9ce047f0/mind-wandering-1200px_web.jpg)

When psychologist Jonathan Smallwood set out to study mind-wandering about 25 years ago, few of his peers thought that was a very good idea. How could one hope to investigate these spontaneous and unpredictable thoughts that crop up when people stop paying attention to their surroundings and the task at hand? Thoughts that couldn’t be linked to any measurable outward behavior?

But Smallwood, now at Queen’s University in Ontario, Canada, forged ahead. He used as his tool a downright tedious computer task that was intended to reproduce the kinds of lapses of attention that cause us to pour milk into someone’s cup when they asked for black coffee. And he started out by asking study participants a few basic questions to gain insight into when and why minds tend to wander, and what subjects they tend to wander toward. After a while, he began to scan participants’ brains as well, to catch a glimpse of what was going on in there during mind-wandering.

Smallwood learned that unhappy minds tend to wander in the past, while happy minds often ponder the future . He also became convinced that wandering among our memories is crucial to help prepare us for what is yet to come. Though some kinds of mind-wandering — such as dwelling on problems that can’t be fixed — may be associated with depression , Smallwood now believes mind-wandering is rarely a waste of time. It is merely our brain trying to get a bit of work done when it is under the impression that there isn’t much else going on.

Smallwood, who coauthored an influential 2015 overview of mind-wandering research in the Annual Review of Psychology, is the first to admit that many questions remain to be answered.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Is mind-wandering the same thing as daydreaming, or would you say those are different?

I think it’s a similar process used in a different context. When you’re on holiday, and you’ve got lots of free time, you might say you’re daydreaming about what you’d like to do next. But when you’re under pressure to perform, you’d experience the same thoughts as mind-wandering.

I think it is more helpful to talk about the underlying processes: spontaneous thought, or the decoupling of attention from perception, which is what happens when our thoughts separate from our perception of the environment. Both these processes take place during mind-wandering and daydreaming.

It often takes us a while to catch ourselves mind-wandering. How can you catch it to study it in other people?

In the beginning, we gave people experimental tasks that were really boring, so that mind-wandering would happen a lot. We would just ask from time to time, “Are you mind-wandering?” while recording the brain’s activity in an fMRI scanner.

But what I’ve realized, after doing studies like that for a long time, is that if we want to know how thinking works in the real world, where people are doing things like watching TV or going for a run, most of the data we have are never going to tell us very much.

So we are now trying to study these situations . And instead of doing experiments where we just ask, “Are you mind-wandering?” we are now asking people a lot of different questions, like: “Are your thoughts detailed? Are they positive? Are they distracting you?”

How and why did you decide to study mind-wandering?

I started studying mind-wandering at the start of my career, when I was young and naive.

I didn’t really understand at the time why nobody was studying it. Psychology was focused on measurable, outward behavior then. I thought to myself: That’s not what I want to understand about my thoughts. What I want to know is: Why do they come, where do they come from, and why do they persist even if they interfere with attention to the here and now?

Around the same time, brain imaging techniques were developing, and they were telling neuroscientists that something happens in the brain even when it isn’t occupied with a behavioral task. Large regions of the brain, now called the default mode network , did the opposite: If you gave people a task, the activity in these areas went down.

When scientists made this link between brain activity and mind-wandering, it became fashionable. I’ve been very lucky, because I hadn’t anticipated any of that when I started my PhD, at the University of Strathclyde in Glasgow. But I’ve seen it all pan out.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/4c/58/4c5891e3-0206-47df-9255-a8d5e196de9f/g-default-mode-network-alt_web.jpg)

Would you say, then, that mind-wandering is the default mode for our brains?

It turns out to be more complicated than that. Initially, researchers were very sure that the default mode network rarely increased its activity during tasks. But these tasks were all externally focused — they involved doing something in the outside world. When researchers later asked people to do a task that doesn’t require them to interact with their environment — like think about the future — that activated the default mode network as well.

More recently, we have identified much simpler tasks that also activate the default mode network. If you let people watch a series of shapes like triangles or squares on a screen, and every so often you surprise them and ask something — like, “In the last trial, which side was the triangle on?”— regions within the default mode network increase activity when they’re making that decision . That’s a challenging observation if you think the default mode network is just a mind-wandering system.

But what both situations have in common is the person is using information from memory. I now think the default mode network is necessary for any thinking based on information from memory — and that includes mind-wandering.

Would it be possible to demonstrate that this is indeed the case?

In a recent study, instead of asking people whether they were paying attention, we went one step further . People were in a scanner reading short factual sentences on a screen. Occasionally, we’d show them a prompt that said, “Remember,” followed by an item from a list of things from their past that they’d provided earlier. So then, instead of reading, they’d remember the thing we showed them. We could cause them to remember.

What we find is that the brain scans in this experiment look remarkably similar to mind-wandering. That is important: It gives us more control over the pattern of thinking than when it occurs spontaneously, like in naturally occurring mind-wandering. Of course, that is a weakness as well, because it’s not spontaneous. But we’ve already done lots of spontaneous studies.

When we make people remember things from the list, we recapitulate quite a lot of what we saw in spontaneous mind-wandering. This suggests that at least some of the activity we see when minds wander is indeed associated with the retrieval of memories. We now think the decoupling between attention and perception happens because people are remembering.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f4/73/f473de94-c653-4155-be90-aa06c5d9a827/g-brain-regions-mind-wandering-alt_web.jpg)

Have you asked people what their minds are wandering toward?

The past and future seem to really dominate people’s thinking . I think things like mind-wandering are attempts by the brain to make sense of what has happened, so that we can behave better in the future. I think this type of thinking is a really ingrained part of how our species has conquered the world. Almost nothing we’re doing at any moment in time can be pinpointed as only mattering then.

That’s a defining difference. By that, I don’t mean that other animals can’t imagine the future, but that our world is built upon our ability to do so, and to learn from the past to build a better future. I think animals that focused only on the present were outcompeted by others that remembered things from the past and could focus on future goals, for millions of years — until you got humans, a species that’s obsessed with taking things that happened and using them to gain added value for future behavior.

People are also, very often, mind-wandering about social situations . This makes sense, because we have to work with other people to achieve almost all of our goals, and other people are much more unpredictable than the Sun rising in the morning.

Though it is clearly useful, isn’t it also very depressing to keep returning to issues from the past?

It certainly can be. We have found that mind-wandering about the past tends to be associated with negative mood.

Let me give you an example of what I think may be happening. For a scientist like me, coming up with creative solutions to scientific problems through mind-wandering is very rewarding. But you can imagine that if my situation changes and I end up with a set of problems I can’t fix, the habit of going over the past may become difficult to break. My brain will keep activating the problem-solving system, even if it can’t do anything to fix the problem, because now my problems are things like getting divorced and my partner doesn’t want any more to do with me. If such a thing happens and all I’ve got is an imaginative problem-solving system, it’s not going to help me, it’s just going to be upsetting. I just have to let it go.

That’s where I think mindfulness could be useful, because the idea of mindfulness is to bring your attention to the moment. So if I’d be more mindful, I’d be going into problem-solving mode less often.

If you spend long enough practicing being in the moment, maybe that becomes a habit. It’s about being able to control your mind-wandering. Cognitive behavioral therapy for depression, which aims to help people change how they think and behave, is another way to reduce harmful mind-wandering.

Nowadays, it seems that many of the idle moments in which our minds would previously have wandered are now spent scrolling our phones. How do you think that might change how our brain functions?

The interesting thing about social media and mind-wandering, I think, is that they may have similar motivations. Mind-wandering is very social. In our studies , we’re locking people in small booths and making them do these tasks and they keep coming out and saying, “I’m thinking about my friends.” That’s telling us that keeping up with others is very important to people.

Social groups are so important to us as a species that we spend most of our time trying to anticipate what others are going to do, and I think social media is filling part of the gap that mind-wandering is trying to fill. It’s like mainlining social information: You can try to imagine what your friend is doing, or you can just find out online. Though, of course, there is an important difference: When you’re mind-wandering, you’re ordering your own thoughts. Scrolling social media is more passive.

Could there be a way for us to suppress mind-wandering in situations where it might be dangerous?

Mind-wandering can be a benefit and a curse, but I wouldn’t be confident that we know yet when it would be a good idea to stop it. In our studies at the moment, we are trying to map how people think across a range of different types of tasks. We hope this approach will help us identify when mind-wandering is likely to be useful or not — and when we should try to control it and when we shouldn’t.

For example, in our studies, people who are more intelligent don’t mind wander so often when the task is hard but can do it more when tasks are easy . It is possible that they are using the idle time when the external world is not demanding their attention to think about other important matters. This highlights the uncertainty about whether mind wandering is always a bad thing, because this sort of result implies it is likely to be useful under some circumstances.

This map — of how people think in different situations — has become very important in our research. This is the work I’m going to focus on now, probably for the rest of my career.

Get the latest Science stories in your inbox.

Let Your Mind Wander

Experience the benefits of daydreaming in creativity and problem solving..

Posted February 20, 2024 | Reviewed by Davia Sills

- Understanding Attention

- Find a therapist to help with ADHD

- Mind wandering is a universal human experience rooted in evolution and brain science.

- Creative thinking and problem-solving happen when people's minds wander.

- Mind wandering also allows individuals to simulate the future and script their range of responses.

Comedian Steven Wright deadpanned, “I was trying to daydream, but my mind kept wandering.” With that quip, he encapsulated the universal human experience of mind wandering .

Our minds are never idle. When not focused on doing a specific task or achieving a goal, we daydream, fantasize , ruminate, reminisce about something in the past, or worry about something in the future.

In fact, research with thought-sampling techniques has shown that an average of 47 percent of our time is spent with our mind wandering. 1 Think of it: nearly half our waking hours!

Research also suggests that mind wandering is not time wasted but a constructive mental tool supporting creativity, problem-solving, and better mood.

Creativity Benefits From Mind Wandering

Mind wandering can be negative and obsessive and present obstacles to accomplishing goals . Left to their own devices, people may gravitate toward the negative.

But that is only part of the story. Many reveries are welcome, playful, creative daydreams to be nourished. Mind wandering allows us to learn from our imagination . Consequently, mind wandering is critical to “creative incubation,” the background mental work that precedes our insightful “Aha!” moments.

In my lab, we have found that broad and unrestrained mind wandering can also promote better mood among people with mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression .

Learning Through Imagined Experience

Memory stores actual experience. It can also hold the outcome of experiences we imagine or simulated scenarios. I’ll give you an example.

While on an airplane flight once, I was reviewing a paper, and my mind drifted until it landed on the emergency door, which triggered the following simulation: What if the door suddenly opens while we are in the air?

I will need a parachute, I thought. I could probably use the airplane blanket on my lap, but I will not be able to hold on to it in the strong wind—it needs holes. I can use my pen to make the holes. And so on.

This story is far-fetched and funny, but nevertheless, I now have, from an imagined experience, a script stored in my memory that would be helpful should the unlikely event ever happen.

We do this often, and not always about possible catastrophes. By fabricating possible future experiences, we have memories that we can call on to navigate our lives and fall back on to guide our behavior in the future.

Wandering Is the Brain’s Default

One of the most meaningful developments in recent neuroscience is the serendipitous discovery of the brain network that hosts our mind wandering: substantial cortical regions clustered together in the brain’s “ default mode network .”

Wandering is what our brain does by default. So, logic dictates that if our brains dedicate so much energy to mind wandering, mind wandering should play an important role.

There is a trade-off, though. With all the benefits of creative thinking , planning, decision-making , and mood, mind wandering takes us away from the present. Evolution seems to have prioritized our ability to survive and flourish over our ability to cherish the moment.

I remember having lunch at a cafe in Tel Aviv with a visiting professor from Stanford. I greatly admire his work and his personality . At one point in our conversation, he told me he had once heard something that had completely changed him, how he thinks, and how he lives his life, and he wanted to share it with me.

I have no idea what it was. Despite his dramatic introduction, my mind drifted far away as he spoke. I was too embarrassed to tell him I hadn’t caught what he’d said once I realized what had happened. I can only imagine how odd he must have thought it was that I didn’t comment meaningfully on what he’d said but quickly changed the subject.

Happily, though, I can report that my mind had wandered to something interesting in my own life. Perverse as our mind wandering can be, at least it generally does have a purpose.

Put a Wandering Mind to Use

Most of what we do regularly involves some creation or production, from making food to fixing a leaky shower, from writing a letter to gardening. Even thinking is an act of creation. New ideas, inventions, and plans you make while your mind wanders are all products your mind created.

While we cannot direct our mind as to what to wander about, we can strive to fill the mental space of possibilities with what we would have liked to wander about, either because we seek new ideas, because it makes us feel good, or both.

Before I go on a long walk or do any other activity that is not overly demanding, I ask myself what is on my mind. If it is something like the bills I just paid or an annoying email, I try to replace it with something I’d rather spend my mind-wandering stretch on instead.

I might reread a paragraph that caught my interest recently. Or I might bring back a problem that engaged me before I gave up on it or warm up the idea of an upcoming trip so I can fine-tune the details as I simulate the future with my mind.

This post was adapted from M indwandering: How Your Constant Mental Drift Can Improve Your Mood and Boost Your Creativity by Moshe Bar, Ph.D.

1. Killingsworth, M. R., & Gilbert, D. T. (2010). A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science, 330(6006), 932. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1192439

Moshe Bar, Ph.D. , is a cognitive neuroscientist and the former Director of the Cognitive Neuroscience Lab at Harvard Medical School and the Massachusetts General Hospital.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How to Let Your Mind Wander

Research suggests that people with freely moving thoughts are happier. Easy, repetitive activities like walking can help get you in the right mindset.

By Malia Wollan

“Sometimes you just want to let your mind go free,” says Julia Kam, a cognitive neuroscientist who directs the Internal Attention Lab at the University of Calgary. Kam became interested in her subject 15 years ago as an undergraduate struggling with her own distracted thoughts during lectures. “I came into the field wanting to find a cure,” she says. But the deeper she got into research, the more she came to appreciate the freedom of an unfocused mind. “When your thoughts are just jumping from one topic to the next without an overarching theme or goal, that can be very liberating,” she says.

Researchers have found that people spend up to 50 percent of their time mind-wandering. Some internal thinking can be detrimental, especially the churning, ruminative sort often associated with depression and anxiety. Try instead to cultivate what psychologists call freely moving thoughts. Such nimble thinking might start with a yearning to see your grandmother, then careen to that feeling you get when looking down at clouds from an airplane, and then suddenly you’re pondering how deep you’d have to bore into the earth below your feet before you hit magma. Research suggests that people who do more of that type of mind-wandering are happier.

Facilitate unconstrained thinking by engaging in an easy, repetitive activity like walking; avoid it during riskier undertakings like driving. You’ll find it harder to go free-ranging if you’re myopically worried about something in your personal life, like an illness or an argument with a spouse.

For a recent study, Kam hooked subjects up for an electroencephalogram and then had them do a mundane task on a keyboard while periodically asking them about their thoughts. She was able to see, for the first time, a distinct neural marker for freely moving thoughts, which caused an increase in alpha waves in the brain’s frontal cortex. This is the same region where scientists see alpha waves in people doing creative problem-solving. We live in a culture that values work and productivity over almost everything else, but remember, your mind is yours. Make space to think in idle ways unrelated to tasks. “It can replenish you,” Kam says.

Explore The New York Times Magazine

Donald Trump’s Rally Rhetoric : No major American presidential candidate has talked like he now does at his rallies — not Richard Nixon, not George Wallace, not even Trump himself.

The King of Tidy Eating : Rapturously messy food reviews are all over the internet. Keith Lee’s discreet eating style rises above them all .

What Are Animals Really Feeling? : Animal-welfare science tries to get inside the minds of a huge range of species — in order to help improve their lives.

Can a Sexless Marriage Be Happy?: Experts and couples are challenging the conventional wisdom that sex is essential to relationships.

Lessons From a 20-Person Polycule : Here’s how they set boundaries , navigate jealousy, wingman their spouses and foster community.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 22 September 2016

Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework

- Kalina Christoff 1 , 2 ,

- Zachary C. Irving 3 ,

- Kieran C. R. Fox 1 ,

- R. Nathan Spreng 4 , 5 &

- Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna 6

Nature Reviews Neuroscience volume 17 , pages 718–731 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

25k Accesses

677 Citations

492 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cognitive control

- Schizophrenia

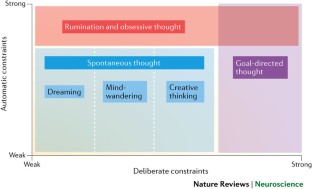

In the past 15 years, mind-wandering has become a prominent topic in cognitive neuroscience and psychology. Whereas mind-wandering has come to be predominantly defined as task-unrelated and/or stimulus-unrelated thought, we argue that this content-based definition fails to capture the defining quality of mind-wandering: the relatively free and spontaneous arising of mental states as the mind wanders.

We define spontaneous thought as a mental state, or a sequence of mental states, that arises relatively freely due to an absence of strong constraints on the contents of each state and on the transitions from one mental state to another. We propose that there are two general ways in which the content of mental states, and the transitions between them, can be constrained.

Deliberate and automatic constraints serve to limit the contents of thought and how these contents change over time. Deliberate constraints are implemented through cognitive control, whereas automatic constraints can be considered as a family of mechanisms that operate outside of cognitive control, including sensory or affective salience.

Within our framework, mind-wandering can be defined as a special case of spontaneous thought that tends to be more deliberately constrained than dreaming, but less deliberately constrained than creative thinking and goal-directed thought. In addition, mind-wandering can be clearly distinguished from rumination and other types of thought that are marked by a high degree of automatic constraints, such as obsessive thought.

In general, deliberate constraints are minimal during dreaming, tend to increase somewhat during mind-wandering, increase further during creative thinking and are strongest during goal-directed thought. There is a range of low-to-medium level of automatic constraints that can occur during dreaming, mind-wandering and creative thinking, but thought ceases to be spontaneous at the strongest levels of automatic constraint, such as during rumination or obsessive thought.

We propose a neural model of the interactions among sources of variability, automatic constraints and deliberate constraints on thought: the default network (DN) subsystem centred around the medial temporal lobe (MTL) (DN MTL ) and sensorimotor areas can act as sources of variability; the salience networks, the dorsal attention network (DAN) and the core DN subsystem (DN CORE ) can exert automatic constraints on the output of the DN MTL and sensorimotor areas, thus limiting the variability of thought; and the frontoparietal control network can exert deliberate constraints on thought by flexibly coupling with the DN CORE , the DAN or the salience networks, thus reinforcing or reducing the automatic constraints being exerted by the DN CORE , the DAN or the salience networks.

Most research on mind-wandering has characterized it as a mental state with contents that are task unrelated or stimulus independent. However, the dynamics of mind-wandering — how mental states change over time — have remained largely neglected. Here, we introduce a dynamic framework for understanding mind-wandering and its relationship to the recruitment of large-scale brain networks. We propose that mind-wandering is best understood as a member of a family of spontaneous-thought phenomena that also includes creative thought and dreaming. This dynamic framework can shed new light on mental disorders that are marked by alterations in spontaneous thought, including depression, anxiety and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

176,64 € per year

only 14,72 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Control of working memory by phase–amplitude coupling of human hippocampal neurons

The language network as a natural kind within the broader landscape of the human brain

James, W. The Principles of Psychology (Henry Holt and Company, 1890).

Google Scholar

Callard, F., Smallwood, J., Golchert, J. & Margulies, D. S. The era of the wandering mind? Twenty-first century research on self-generated mental activity. Front. Psychol. 4 , 891 (2013).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Andreasen, N. C. et al. Remembering the past: two facets of episodic memory explored with positron emission tomography. Am. J. Psychiatry 152 , 1576–1585 (1995).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Binder, J. R., Frost, J. A. & Hammeke, T. A. Conceptual processing during the conscious resting state: a functional MRI study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 11 , 80–93 (1999).

Stark, C. E. & Squire, L. R. When zero is not zero: the problem of ambiguous baseline conditions in fMRI. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 12760–12766 (2001).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Christoff, K. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. The frontopolar cortex and human cognition: evidence for a rostrocaudal hierarchical organization within the human prefrontal cortex. Psychobiology 28 , 168–186 (2000).

Shulman, G. L. et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks: II. Decreases cerebral cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 9 , 648–663 (1997). This meta-analysis provides convincing evidence that a set of specific brain regions, which later became known as the default mode network, becomes consistently activated during rest.

Raichle, M. E. et al. A default mode of brain function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98 , 676–682 (2001). This highly influential theoretical paper coined the term 'default mode' to refer to cognitive and neural processes that occur in the absence of external task demands.

Singer, J. L. Daydreaming: An Introduction to the Experimental Study of Inner Experience (Random House, 1966).

Antrobus, J. S. Information theory and stimulus-independent thought. Br. J. Psychol. 59 , 423–430 (1968).

Antrobus, J. S., Singer, J. L., Goldstein, S. & Fortgang, M. Mind wandering and cognitive structure. Trans. NY Acad. Sci. 32 , 242–252 (1970).

CAS Google Scholar

Filler, M. S. & Giambra, L. M. Daydreaming as a function of cueing and task difficulty. Percept. Mot. Skills 37 , 503–509 (1973).

Giambra, L. M. Adult male daydreaming across the life span: a replication, further analyses, and tentative norms based upon retrospective reports. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 8 , 197–228 (1977).

PubMed Google Scholar

Giambra, L. M. Sex differences in daydreaming and related mental activity from the late teens to the early nineties. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 10 , 1–34 (1979).

Klinger, E. & Cox, W. M. Dimensions of thought flow in everyday life. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 7 , 105–128 (1987). This is probably the earliest experience sampling study of mind-wandering in daily life, revealing that adults spend approximately one-third of their waking life engaged in undirected thinking.

Giambra, L. M. Task-unrelated-thought frequency as a function of age: a laboratory study. Psychol. Aging 4 , 136–143 (1989).

Teasdale, J. D., Proctor, L., Lloyd, C. A. & Baddeley, A. D. Working memory and stimulus-independent thought: effects of memory load and presentation rate. Eur. J. Cogn. Psychol. 5 , 417–433 (1993).

Giambra, L. M. A laboratory method for investigating influences on switching attention to task-unrelated imagery and thought. Conscious. Cogn. 4 , 1–21 (1995).

Klinger, E. Structure and Functions of Fantasy (John Wiley & Sons, 1971). This pioneering book summarizes the early empirical research on daydreaming and introduces important theoretical hypotheses, including the idea that task-unrelated thoughts are often about 'current concerns'.

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The restless mind. Psychol. Bull. 132 , 946–958 (2006). This paper put mind-wandering in the forefront of psychological research, advancing the influential hypothesis that executive resources support mind-wandering.

Killingsworth, M. A. & Gilbert, D. T. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science 330 , 932 (2010).

Mason, M. F. et al. Wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science 315 , 393–395 (2007). This influential paper brought mind-wandering to the forefront of neuroscientific research, arguing for a link between DN recruitment and stimulus-independent thought.

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M., Smallwood, J., Smith, R. & Schooler, J. W. Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 8719–8724 (2009). This paper is the first to use online experience sampling to examine the neural correlates of mind-wandering and the first to find joint activation of the DN and executive network during this phenomenon.

Callard, F., Smallwood, J. & Margulies, D. S. Default positions: how neuroscience's historical legacy has hampered investigation of the resting mind. Front. Psychol. 3 , 321 (2012).

Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. The science of mind wandering: empirically navigating the stream of consciousness. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 66 , 487–518 (2015). This comprehensive review synthesizes the recent research characterizing mind-wandering as task-unrelated and/or stimulus-independent thought.

Christoff, K. Undirected thought: neural determinants and correlates. Brain Res. 1428 , 51–59 (2012). This review disambiguates between different definitions of spontaneous thought and mind-wandering, and it argues that current definitions do not capture the dynamics of thought.

Irving, Z. C. Mind-wandering is unguided attention: accounting for the 'purposeful' wanderer. Philos. Stud. 173 , 547–571 (2016). This is one of the first philosophical theories of mind-wandering; this paper defines mind-wandering as unguided attention to explain why its dynamics contrast with automatically and deliberately guided forms of attention such as rumination and goal-directed thinking.

Carruthers, P. The Centered Mind: What the Science of Working Memory Shows Us About the Nature of Human Thought (Oxford Univ. Press, 2015).

Simpson, J. A. The Oxford English Dictionary (Clarendon Press, 1989).

Kane, M. J. et al. For whom the mind wanders, and when: an experience-sampling study of working memory and executive control in daily life. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 614–621 (2007). This study of mind-wandering in everyday life is one of the most important investigations into the complex relationship between mind-wandering and executive control.

Baird, B., Smallwood, J. & Schooler, J. W. Back to the future: autobiographical planning and the functionality of mind-wandering. Conscious. Cogn. 20 , 1604–1611 (2011).

Morsella, E., Ben-Zeev, A., Lanska, M. & Bargh, J. A. The spontaneous thoughts of the night: how future tasks breed intrusive cognitions. Social Cogn. 28 , 641–650 (2010).

Miller, E. K. & Cohen, J. D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24 , 167–202 (2001).

Miller, E. K. The prefrontal cortex and cognitive control. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1 , 59–65 (2000).

Markovic, J., Anderson, A. K. & Todd, R. M. Tuning to the significant: neural and genetic processes underlying affective enhancement of visual perception and memory. Behav. Brain Res. 259 , 229–241 (2014).

Todd, R. M., Cunningham, W. A., Anderson, A. K. & Thompson, E. Affect-biased attention as emotion regulation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 365–372 (2012).

Pessoa, L. The Cognitive-Emotional Brain: From Interactions to Integration (MIT Press, 2013).

Jonides, J. & Yantis, S. Uniqueness of abrupt visual onset in capturing attention. Percept. Psychophys. 43 , 346–354 (1988).

Christoff, K., Gordon, A. M. & Smith, R. in Neuroscience of Decision Making (eds Vartanian, O. & Mandel, D. R.) 259–284 (Psychology Press, 2011).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maj, M., Van der Linden, M. & D'Argembeau, A. Mind-wandering: phenomenology and function as assessed with a novel experience sampling method. Acta Psychol. (Amst.) 136 , 370–381 (2011).

Spreng, R. N., Mar, R. A. & Kim, A. S. N. The common neural basis of autobiographical memory, prospection, navigation, theory of mind, and the default mode: a quantitative meta-analysis. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 21 , 489–510 (2009). This paper provides some of the first quantitative evidence that the DN is associated with multiple cognitive functions.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R. The brain's default network and its adaptive role in internal mentation. Neuroscientist 18 , 251–270 (2012). This recent review describes a large-scale functional meta-analysis on the cognitive functions, functional subdivisions and clinical dysfunction of the DN.

Buckner, R. L. & Carroll, D. C. Self-projection and the brain. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11 , 49–57 (2007).

Buckner, R. L., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Schacter, D. L. The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124 , 1–38 (2008). This comprehensive review bridges across neuroscience, psychology and clinical research, and introduces a prominent hypothesis — the 'internal mentation hypothesis' — that the DN has an important role in spontaneous and directed forms of internal mentation.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Sepulcre, J., Poulin, R. & Buckner, R. L. Functional-anatomic fractionation of the brain's default network. Neuron 65 , 550–562 (2010).

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R. & Buckner, R. L. Remembering the past to imagine the future: the prospective brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 657–661 (2007).

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Smallwood, J. & Spreng, R. N. The default network and self-generated thought: component processes, dynamic control, and clinical relevance. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1316 , 29–52 (2014).

Corbetta, M., Patel, G. & Shulman, G. L. The reorienting system of the human brain: from environment to theory of mind. Neuron 58 , 306–324 (2008). This paper outlines an influential theoretical framework that extends an earlier model by Corbetta and Shulman that drew a crucial distinction between the DAN and VAN.

Vanhaudenhuyse, A. et al. Two distinct neuronal networks mediate the awareness of environment and of self. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 570–578 (2011).

Smallwood, J. Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: a process–occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol. Bull. 139 , 519–535 (2013). This theoretical paper presents an important distinction between the events that determine when an experience initially occurs from the processes that sustain an experience over time.

Toro, R., Fox, P. T. & Paus, T. Functional coactivation map of the human brain. Cereb. Cortex 18 , 2553–2559 (2008).

Fox, M. D. et al. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 9673–9678 (2005). This paper provides a unique insight into the functional antagonism between the default and dorsal attention systems.

CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Keller, C. J. et al. Neurophysiological investigation of spontaneous correlated and anticorrelated fluctuations of the BOLD signal. J. Neurosci. 33 , 6333–6342 (2013).

Seeley, W. W. et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J. Neurosci. 27 , 2349–2356 (2007). This paper is the first to name the salience network and characterize its functional neuroanatomy.

Kucyi, A., Hodaie, M. & Davis, K. D. Lateralization in intrinsic functional connectivity of the temporoparietal junction with salience- and attention-related brain networks. J. Neurophysiol. 108 , 3382–3392 (2012).

Power, J. D. et al. Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron 72 , 665–678 (2011).

Cole, M. W. et al. Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 1348–1355 (2013).

Vincent, J. L., Kahn, I., Snyder, A. Z., Raichle, M. E. & Buckner, R. L. Evidence for a frontoparietal control system revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 100 , 3328–3342 (2008).

Niendam, T. A. et al. Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 12 , 241–268 (2012).

Spreng, R. N., Stevens, W. D., Chamberlain, J. P., Gilmore, A. W. & Schacter, D. L. Default network activity, coupled with the frontoparietal control network, supports goal-directed cognition. Neuroimage 53 , 303–317 (2010). This paper demonstrates how the DN couples with the FPCN for personally salient, goal-directed information processing.

Dixon, M. L., Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. A framework for understanding the relationship between externally and internally directed cognition. Neuropsychologia 62 , 321–330 (2014).

Dosenbach, N. U. F. et al. A core system for the implementation of task sets. Neuron 50 , 799–812 (2006).

Dosenbach, N. U. F. et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 11073–11078 (2007).

Dosenbach, N. U. F., Fair, D. A., Cohen, A. L., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn. Sci. 12 , 99–105 (2008).

Yeo, B. T. T. et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J. Neurophysiol. 106 , 1125–1165 (2011). This seminal paper uses resting-state functional connectivity and clustering approaches in 1,000 individuals to parcellate the brain into seven canonical large-scale networks.

Najafi, M., McMenamin, B. W., Simon, J. Z. & Pessoa, L. Overlapping communities reveal rich structure in large-scale brain networks during rest and task conditions. Neuroimage 135 , 92–106 (2016).

McGuire, P. K., Paulesu, E., Frackowiak, R. S. & Frith, C. D. Brain activity during stimulus independent thought. Neuroreport 7 , 2095–2099 (1996).

McKiernan, K. A., D'Angelo, B. R., Kaufman, J. N. & Binder, J. R. Interrupting the 'stream of consciousness': an fMRI investigation. Neuroimage 29 , 1185–1191 (2006).

Gilbert, S. J., Dumontheil, I., Simons, J. S., Frith, C. D. & Burgess, P. W. Comment on 'wandering minds: the default network and stimulus-independent thought'. Science 317 , 43b (2007).

Stawarczyk, D., Majerus, S., Maquet, P. & D'Argembeau, A. Neural correlates of ongoing conscious experience: both task-unrelatedness and stimulus-independence are related to default network activity. PLoS ONE 6 , e16997 (2011).

Fox, K. C. R., Spreng, R. N., Ellamil, M., Andrews-Hanna, J. R. & Christoff, K. The wandering brain: meta-analysis of functional neuroimaging studies of mind-wandering and related spontaneous thought processes. Neuroimage 111 , 611–621 (2015). This paper presents the first quantitative meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on task-unrelated and/or stimulus-independent thought, revealing the involvement of the DN and other large-scale networks that were not traditionally thought to play a part in mind-wandering.

Ingvar, D. H. 'Hyperfrontal' distribution of the cerebral grey matter flow in resting wakefulness; on the functional anatomy of the conscious state. Acta Neurol. Scand. 60 , 12–25 (1979). This paper by David Ingvar, a pioneer of human neuroimaging, provides the original observations that a resting brain is an active one and highlights the finding that prefrontal executive regions are active even at rest.

Christoff, K., Ream, J. M. & Gabrieli, J. D. E. Neural basis of spontaneous thought processes. Cortex 40 , 623–630 (2004).

D'Argembeau, A. et al. Self-referential reflective activity and its relationship with rest: a PET study. Neuroimage 25 , 616–624 (2005).

Spiers, H. J. & Maguire, E. A. Spontaneous mentalizing during an interactive real world task: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 44 , 1674–1682 (2006).

Wang, K. et al. Offline memory reprocessing: involvement of the brain's default network in spontaneous thought processes. PLoS ONE 4 , e4867 (2009).

Dumontheil, I., Gilbert, S. J., Frith, C. D. & Burgess, P. W. Recruitment of lateral rostral prefrontal cortex in spontaneous and task-related thoughts. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 63 , 1740–1756 (2010).

Posner, M. I. & Rothbart, M. K. Attention, self-regulation and consciousness. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 353 , 1915–1927 (1998).

Duncan, J. & Owen, A. M. Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 23 , 475–483 (2000).

Botvinick, M. M., Braver, T. S., Barch, D. M., Carter, C. S. & Cohen, J. D. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychol. Rev. 108 , 624–652 (2001).

Banich, M. T. Executive function: the search for an integrated account. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 89–94 (2009).

Prado, J., Chadha, A. & Booth, J. R. The brain network for deductive reasoning: a quantitative meta-analysis of 28 neuroimaging studies. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 3483–3497 (2011).

McVay, J. C. & Kane, M. J. Does mind wandering reflect executive function or executive failure? Comment on Smallwood and Schooler (2006) and Watkins (2008). Psychol. Bull. 136 , 188–197 (2010). This paper presents the theoretically influential control failure hypothesis, which is opposed to the thesis that executive function supports mind-wandering.

Kane, M. J. & McVay, J. C. What mind wandering reveals about executive-control abilities and failures. Curr. Direct. Psychol. Sci. 21 , 348–354 (2012).

Levinson, D. B., Smallwood, J. & Davidson, R. J. The persistence of thought: evidence for a role of working memory in the maintenance of task-unrelated thinking. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 375–380 (2012).

Salthouse, T. A., Fristoe, N., McGuthry, K. E. & Hambrick, D. Z. Relation of task switching to speed, age, and fluid intelligence. Psychol. Aging 13 , 445–461 (1998).

Maillet, D. & Schacter, D. L. From mind wandering to involuntary retrieval: age-related differences in spontaneous cognitive processes. Neuropsychologia 80 , 142–156 (2016).

Axelrod, V., Rees, G., Lavidor, M. & Bar, M. Increasing propensity to mind-wander with transcranial direct current stimulation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112 , 3314–3319 (2015).

Schooler, J. W. et al. Meta-awareness, perceptual decoupling and the wandering mind. Trends Cogn. Sci. 15 , 319–326 (2011).

Smallwood, J., Beach, E. & Schooler, J. W. Going AWOL in the brain: mind wandering reduces cortical analysis of external events. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 20 , 458–469 (2008).

Kam, J. W. Y. et al. Slow fluctuations in attentional control of sensory cortex. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 23 , 460–470 (2011).

Gelbard-Sagiv, H., Mukamel, R., Harel, M., Malach, R. & Fried, I. Internally generated reactivation of single neurons in human hippocampus during free recall. Science 322 , 96–101 (2008). This pioneering study aimed to identify the neural origins of spontaneously recalled memories, finding strong evidence for the initial generation in the MTL.

Ellamil, M. et al. Dynamics of neural recruitment surrounding the spontaneous arising of thoughts in experienced mindfulness practitioners. Neuroimage 136 , 186–196 (2016). This study is the first to reveal a sequential recruitment of the DN MTL , DN CORE , and FPCN immediately before, during and subsequent to the onset of spontaneous thoughts.

Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Reidler, J. S., Huang, C. & Buckner, R. L. Evidence for the default network's role in spontaneous cognition. J. Neurophysiol. 104 , 322–335 (2010).

Kucyi, A. & Davis, K. D. Dynamic functional connectivity of the default mode network tracks daydreaming. Neuroimage 100 , 471–480 (2014).

Foster, D. J. & Wilson, M. A. Reverse replay of behavioural sequences in hippocampal place cells during the awake state. Nature 440 , 680–683 (2006).

Karlsson, M. P. & Frank, L. M. Awake replay of remote experiences in the hippocampus. Nat. Neurosci. 12 , 913–918 (2009).

Carr, M. F., Jadhav, S. P. & Frank, L. M. Hippocampal replay in the awake state: a potential substrate for memory consolidation and retrieval. Nat. Neurosci. 14 , 147–153 (2011).

Dragoi, G. & Tonegawa, S. Distinct preplay of multiple novel spatial experiences in the rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110 , 9100–9105 (2013).

Dragoi, G. & Tonegawa, S. Preplay of future place cell sequences by hippocampal cellular assemblies. Nature 469 , 397–401 (2011).

Ólafsdóttir, H. F., Barry, C., Saleem, A. B. & Hassabis, D. Hippocampal place cells construct reward related sequences through unexplored space. eLife 4 , e06063 (2015).

Stark, C. E. L. & Clark, R. E. The medial temporal lobe. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27 , 279–306 (2004).

Moscovitch, M., Cabeza, R., Winocur, G. & Nadel, L. Episodic memory and beyond: the hippocampus and neocortex in transformation. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 67 , 105–134 (2016).

Romero, K. & Moscovitch, M. Episodic memory and event construction in aging and amnesia. J. Mem. Lang. 67 , 270–284 (2012).

Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D. & Maguire, E. A. Using imagination to understand the neural basis of episodic memory. J. Neurosci. 27 , 14365–14374 (2007).

Buckner, R. L. The role of the hippocampus in prediction and imagination. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 61 , 27–48 (2010).

Hassabis, D. & Maguire, E. A. The construction system of the brain. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364 , 1263–1271 (2009).

Schacter, D. L. et al. The future of memory: remembering, imagining, and the brain. Neuron 76 , 677–694 (2012).

Schacter, D. L., Addis, D. R. & Buckner, R. L. Episodic simulation of future events: concepts, data, and applications. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1124 , 39–60 (2008).

Moscovitch, M. Memory and working-with-memory: a component process model based on modules and central systems. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 4 , 257–267 (1992). This paper introduces the influential component process model of memory.

Teyler, T. J. & DiScenna, P. The hippocampal memory indexing theory. Behav. Neurosci. 100 , 147–154 (1986).

Moscovitch, M. The hippocampus as a “stupid,” domain-specific module: implications for theories of recent and remote memory, and of imagination. Can. J. Exp. Psychol. 62 , 62–79 (2008).

Bar, M., Aminoff, E., Mason, M. & Fenske, M. The units of thought. Hippocampus 17 , 420–428 (2007). This paper introduces a novel hypothesis on the associative processes underlying a train of thoughts, originating in the MTL.

Aminoff, E. M., Kveraga, K. & Bar, M. The role of the parahippocampal cortex in cognition. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 , 379–390 (2013).

Christoff, K., Keramatian, K., Gordon, A. M., Smith, R. & Mädler, B. Prefrontal organization of cognitive control according to levels of abstraction. Brain Res. 1286 , 94–105 (2009).

Dixon, M. L., Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. Evidence for rostro-caudal functional organization in multiple brain areas related to goal-directed behavior. Brain Res. 1572 , 26–39 (2014).

McCaig, R. G., Dixon, M., Keramatian, K., Liu, I. & Christoff, K. Improved modulation of rostrolateral prefrontal cortex using real-time fMRI training and meta-cognitive awareness. Neuroimage 55 , 1298–1305 (2011).

Dixon, M. L. & Christoff, K. The decision to engage cognitive control is driven by expected reward-value: neural and behavioral evidence. PLoS ONE 7 , e51637 (2012).

Yin, H. H. & Knowlton, B. J. The role of the basal ganglia in habit formation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7 , 464–476 (2006).

Burguière. E., Monteiro, P., Mallet, L., Feng, G. & Graybiel, A. M. Striatal circuits, habits, and implications for obsessive–compulsive disorder. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 30 , 59–65 (2015).

Mathews, A. & MacLeod, C. Cognitive vulnerability to emotional disorders. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 1 , 167–195 (2005).

Gotlib, I. H. & Joormann, J. Cognition and depression: current status and future directions. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 6 , 285–312 (2010).

Nolen-Hoeksema, S., Wisco, B. E. & Lyubomirsky, S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 3 , 400–424 (2008).

Watkins, E. R. Constructive and unconstructive repetitive thought. Psychol. Bull. 134 , 163–206 (2008). This comprehensive review and theory article links the psychological literature on task-unrelated or stimulus-independent thought to the clinical literature on rumination and other forms of repetitive thought, proposing multiple factors that govern whether repetitive thought is constructive or unconstructive.

Giambra, L. M. & Traynor, T. D. Depression and daydreaming; an analysis based on self-ratings. J. Clin. Psychol. 34 , 14–25 (1978).

Larsen, R. J. & Cowan, G. S. Internal focus of attention and depression: a study of daily experience. Motiv. Emot. 12 , 237–249 (1988).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. & Ford, J. M. Default mode network activity and connectivity in psychopathology. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 8 , 49–76 (2012).

Anticevic, A. et al. The role of default network deactivation in cognition and disease. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 584–592 (2012).

Hamilton, J. P. et al. Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of baseline activation and neural response data. Am. J. Psychiatry 169 , 693–703 (2012).

Kaiser, R. H. et al. Distracted and down: neural mechanisms of affective interference in subclinical depression. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 10 , 654–663 (2015).

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Wager, T. D. & Pizzagalli, D. A. Large-scale network dysfunction in major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 72 , 603–637 (2015). This meta-analysis of resting-state functional connectivity studies in major depressive disorder provides quantitative support for functional-network imbalances, which reflect heightened internally focused thought in this disorder.

Kaiser, R. H. et al. Dynamic resting-state functional connectivity in major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 41 , 1822–1830 (2015).

Spinhoven, P., Drost, J., van Hemert, B. & Penninx, B. W. Common rather than unique aspects of repetitive negative thinking are related to depressive and anxiety disorders and symptoms. J. Anxiety Disord. 33 , 45–52 (2015).

Borkovec, T. D., Ray, W. J. & Stober, J. Worry: a cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioral processes. Cognit. Ther. Res. 22 , 561–576 (1998).

Oathes, D. J., Patenaude, B., Schatzberg, A. F. & Etkin, A. Neurobiological signatures of anxiety and depression in resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging. Biol. Psychiatry 77 , 385–393 (2015).

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. & van IJzendoorn, M. H. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychol. Bull. 133 , 1–24 (2007).

Williams, J., Watts, F. N., MacLeod, C. & Mathews, A. Cognitive Psychology and Emotional Disorders (John Wiley & Sons, 1997).

Etkin, A., Prater, K. E., Schatzberg, A. F., Menon, V. & Greicius, M. D. Disrupted amygdalar subregion functional connectivity and evidence of a compensatory network in generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 66 , 1361–1372 (2009).

Ipser, J. C., Singh, L. & Stein, D. J. Meta-analysis of functional brain imaging in specific phobia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 67 , 311–322 (2013).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Boonstra, A. M., Oosterlaan, J., Sergeant, J. A. & Buitelaar, J. K. Executive functioning in adult ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Med. 35 , 1097–1108 (2005).

Willcutt, E. G., Doyle, A. E., Nigg, J. T., Faraone, S. V. & Pennington, B. F. Validity of the executive function theory of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analytic review. Biol. Psychiatry 57 , 1336–1346 (2005).

Kofler, M. J. et al. Reaction time variability in ADHD: a meta-analytic review of 319 studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 33 , 795–811 (2013).

Shaw, G. A. & Giambra, L. Task unrelated thoughts of college students diagnosed as hyperactive in childhood. Dev. Neuropsychol. 9 , 17–30 (1993).

Franklin, M. S. et al. Tracking distraction: the relationship between mind-wandering, meta-awareness, and ADHD symptomatology. J. Atten. Disord. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1087054714543494 (2014).

De La Fuente, A., Xia, S., Branch, C. & Li, X. A review of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from the perspective of brain networks. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 192 (2013).

Castellanos, F. X. & Proal, E. Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal–striatal model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 , 17–26 (2012).

Hart, H., Radua, J., Mataix-Cols, D. & Rubia, K. Meta-analysis of fMRI studies of timing in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 36 , 2248–2256 (2012).

Hart, H., Radua, J., Nakao, T., Mataix-Cols, D. & Rubia, K. Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 185–198 (2013).

Fassbender, C. et al. A lack of default network suppression is linked to increased distractibility in ADHD. Brain Res. 1273 , 114–128 (2009).

Cortese, S. et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 169 , 1038–1055 (2012).

Castellanos, F. X. et al. Cingulate-precuneus interactions: a new locus of dysfunction in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 63 , 332–337 (2008).

Uddin, L. Q. et al. Network homogeneity reveals decreased integrity of default-mode network in ADHD. J. Neurosci. Methods 169 , 249–254 (2008).

Tomasi, D. & Volkow, N. D. Abnormal functional connectivity in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 71 , 443–450 (2012).

Mattfeld, A. T. et al. Brain differences between persistent and remitted attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Brain 137 , 2423–2428 (2014).

Sun, L. et al. Abnormal functional connectivity between the anterior cingulate and the default mode network in drug-naïve boys with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 201 , 120–127 (2012).

McCarthy, H. et al. Attention network hypoconnectivity with default and affective network hyperconnectivity in adults diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in childhood. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 1329–1337 (2013).

Fair, D. A. et al. The maturing architecture of the brain's default network. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 , 4028–4032 (2008).

Sripada, C. et al. Disrupted network architecture of the resting brain in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Hum. Brain Mapp. 35 , 4693–4705 (2014). By analysing data from more than 750 participants, this paper links childhood ADHD to abnormal resting-state functional connectivity involving the DN.

Fair, D. A. et al. Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 68 , 1084–1091 (2010).

Anderson, A. et al. Non-negative matrix factorization of multimodal MRI, fMRI and phenotypic data reveals differential changes in default mode subnetworks in ADHD. Neuroimage 102 , 207–219 (2014).

Power, J. D., Barnes, K. A., Snyder, A. Z., Schlaggar, B. L. & Petersen, S. E. Spurious but systematic correlations in functional connectivity MRI networks arise from subject motion. Neuroimage 59 , 2142–2154 (2012).

Van Dijk, K. R. A., Sabuncu, M. R. & Buckner, R. L. The influence of head motion on intrinsic functional connectivity MRI. Neuroimage 59 , 431–438 (2012).

Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. & Castellanos, F. X. Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: a neurobiological hypothesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 31 , 977–986 (2007).

Kerns, J. G. & Berenbaum, H. Cognitive impairments associated with formal thought disorder in people with schizophrenia. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 111 , 211–224 (2002).

Videbeck, S. L. Psychiatric Mental Health Nursing (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006).

Hales, R. E., Yudofsky, S. C. & Roberts, L. W. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry 6th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2014).

Haijma, S. V. et al. Brain volumes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis in over 18 000 subjects. Schizophr. Bull. 39 , 1129–1138 (2013).

Glahn, D. C. et al. Meta-analysis of gray matter anomalies in schizophrenia: application of anatomic likelihood estimation and network analysis. Biol. Psychiatry 64 , 774–781 (2008).

Fornito, A., Yücel, M., Patti, J., Wood, S. J. & Pantelis, C. Mapping grey matter reductions in schizophrenia: an anatomical likelihood estimation analysis of voxel-based morphometry studies. Schizophr. Res. 108 , 104–113 (2009).

Ellison-Wright, I. & Bullmore, E. Anatomy of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 117 , 1–12 (2010).

Vita, A., De Peri, L., Deste, G., Barlati, S. & Sacchetti, E. The effect of antipsychotic treatment on cortical gray matter changes in schizophrenia: does the class matter? A meta-analysis and meta-regression of longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol. Psychiatry 78 , 403–412 (2015).

Cole, M. W., Anticevic, A., Repovs, G. & Barch, D. Variable global dysconnectivity and individual differences in schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatry 70 , 43–50 (2011).

Argyelan, M. et al. Resting-state fMRI connectivity impairment in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Schizophr. Bull. 40 , 100–110 (2014).

Cole, M. W., Yarkoni, T., Repovs, G., Anticevic, A. & Braver, T. S. Global connectivity of prefrontal cortex predicts cognitive control and intelligence. J. Neurosci. 32 , 8988–8999 (2012).

Baker, J. T. et al. Disruption of cortical association networks in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 71 , 109–110 (2014).

Karbasforoushan, H. & Woodward, N. D. Resting-state networks in schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 12 , 2404–2414 (2013).

Jafri, M. J., Pearlson, G. D., Stevens, M. & Calhoun, V. D. A method for functional network connectivity among spatially independent resting-state components in schizophrenia. Neuroimage 39 , 1666–1681 (2008).

Whitfield-Gabrieli, S. et al. Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106 , 1279–1284 (2009).

Palaniyappan, L., Simmonite, M., White, T. P., Liddle, E. B. & Liddle, P. F. Neural primacy of the salience processing system in schizophrenia. Neuron 79 , 814–828 (2013).

Mittner, M., Hawkins, G. E., Boekel, W. & Forstmann, B. U. A neural model of mind wandering. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20 , 570–578 (2016). This paper convincingly argues for the introduction of two important novel elements to the scientific study of mind-wandering: employing cognitive modelling and a consideration of neuromodulatory influences on thought.

Fox, K. C. R. & Christoff, K. in The Cognitive Neuroscience of Metacognition (eds Fleming, S. M. & Frith, C. D.) 293–319 (Springer, 2014).

Foulkes, D. & Fleisher, S. Mental activity in relaxed wakefulness. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 84 , 66–75 (1975).

Fox, K. C. R., Nijeboer, S., Solomonova, E., Domhoff, G. W. & Christoff, K. Dreaming as mind wandering: evidence from functional neuroimaging and first-person content reports. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 412 (2013).

De Bono, E. Six Thinking Hats (Little Brown and Company, 1985).

Ellamil, M., Dobson, C., Beeman, M. & Christoff, K. Evaluative and generative modes of thought during the creative process. Neuroimage 59 , 1783–1794 (2012).

Beaty, R. E., Benedek, M., Kaufman, S. B. & Silvia, P. J. Default and executive network coupling supports creative idea production. Sci. Rep. 5 , 10964 (2015).

Fox, K. C. R., Kang, Y., Lifshitz, M. & Christoff, K. in Hypnosis and Meditation (eds Raz, A. & Lifshitz, M.) 191–210 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Fazelpour, S. & Thompson, E. The Kantian brain: brain dynamics from a neurophenomenological perspective. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 31 , 223–229 (2015).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to R. Buckner, P. Carruthers, M. Cuddy-Keane, M. Dixon, S. Fazelpour, D. Stan, E. Thompson, R. Todd and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback on earlier versions of this paper, and to A. Herrera-Bennett for help with the figure preparation. K.C. was supported by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) (RGPIN 327317–11) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-115197). Z.C.I. was supported by a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC) postdoctoral fellowship, the Balzan Styles of Reasoning Project and a Templeton Integrated Philosophy and Self Control grant. K.C.R.F. was supported by a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship. R.N.S. was supported by an Alzheimer's Association grant (NIRG-14-320049). J.R.A.-H. was supported by a Templeton Science of Prospection grant.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, University of British Columbia, 2136 West Mall, Vancouver, V6T 1Z4, British Columbia, Canada

Kalina Christoff & Kieran C. R. Fox

Centre for Brain Health, University of British Columbia, 2211 Wesbrook Mall, Vancouver, V6T 2B5, British Columbia, Canada

Kalina Christoff

Departments of Philosophy and Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, 94720, California, USA

Zachary C. Irving

Department of Human Development, Laboratory of Brain and Cognition, Cornell University,

R. Nathan Spreng

Human Neuroscience Institute, Cornell University, Ithaca, 14853, New York, USA

Institute of Cognitive Science, University of Colorado Boulder, UCB 594, Boulder, 80309–0594, Colorado, USA

Jessica R. Andrews-Hanna

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kalina Christoff .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, powerpoint slide for fig. 2, powerpoint slide for fig. 3, powerpoint slide for fig. 4, powerpoint slide for fig. 5.

A mental state, or a sequence of mental states, including the transitions that lead to each state.

A transient cognitive or emotional state of the organism that can be described in terms of its contents (what the state is 'about') and the relation that the subject bears to the contents (for example, perceiving, believing, fearing, imagining or remembering).

Thoughts with contents that are unrelated to what the person having those thoughts is currently doing.

Thinking that is characteristically fanciful (that is, divorced from physical or social reality); it can either be spontaneous, as in fanciful mind-wandering, or constrained, as during deliberately fantasizing about a topic.

A thought with contents that are unrelated to the current external perceptual environment.

A deliberate guidance of current thoughts, perceptions or actions, which is imposed in a goal-directed manner by currently active top-down executive processes.

The emotional significance of percepts, thoughts or other elements of mental experience, which can draw and sustain attention through mechanisms outside of cognitive control.

Features of current perceptual experience, such as high perceptual contrast, which can draw and sustain attention through mechanisms outside of cognitive control.

The process of spontaneously or deliberately inferring one's own or other agents' mental states.

Flexible combinations of distinct elements of prior experiences, constructed in the process of imagining a novel (often future-oriented) event.

A type of dreaming during which the dreamer is aware that he or she is currently dreaming and, in some cases, can have deliberate control over dream content and progression.

The ability to produce ideas that are both novel (that is, original and unique) and useful (that is, appropriate and meaningful).

A method in which participants are probed at random intervals and asked to report on aspects of their subjective experience immediately before the probe.

Different ways of categorizing a thought based on its contents, including stimulus dependence (whether the thought is about stimuli that one is currently perceiving), task relatedness (whether the thought is about the current task), modality (visual, auditory, and so on), valence (whether the thought is negative, neutral or positive) or temporal orientation (whether the thought is about the past, present or future).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Christoff, K., Irving, Z., Fox, K. et al. Mind-wandering as spontaneous thought: a dynamic framework. Nat Rev Neurosci 17 , 718–731 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Download citation

Published : 22 September 2016

Issue Date : November 2016

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.113

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Evidence synthesis indicates contentless experiences in meditation are neither truly contentless nor identical.

- Toby J. Woods

- Jennifer M. Windt

- Olivia Carter

Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences (2024)

The mediating role of default mode network during meaning-making aroused by mental simulation between stressful events and stress-related growth: a task fMRI study

Behavioral and Brain Functions (2023)

The role of memory in creative ideation

- Mathias Benedek

- Roger E. Beaty

- Yoed N. Kenett

Nature Reviews Psychology (2023)

A tripartite view of the posterior cingulate cortex

- Brett L. Foster

- Seth R. Koslov

- Sarah R. Heilbronner

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2023)

Effect of subconscious changes in bodily response on thought shifting in people with accurate interoception

- Mai Sakuragi

- Kazushi Shinagawa

- Satoshi Umeda

Scientific Reports (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

It’s normal for your mind to wander. Here’s how to maximise the benefits

Psychology researcher, Bond University

Associate Professor in Psychology, Bond University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Bond University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Have you ever found yourself thinking about loved ones during a boring meeting? Or going over the plot of a movie you recently watched during a drive to the supermarket?

This is the cognitive phenomenon known as “ mind wandering ”. Research suggests it can account for up to 50% of our waking cognition (our mental processes when awake) in both western and non-western societies .

So what can help make this time productive and beneficial?

Mind wandering is not daydreaming

Mind wandering is often used interchangeably with daydreaming. They are both considered types of inattention but are not the same thing.

Mind wandering is related to a primary task, such as reading a book, listening to a lecture, or attending a meeting. The mind withdraws from that task and focuses on internally generated, unrelated thoughts.

On the other hand, daydreaming does not involve a primary, active task. For example, daydreaming would be thinking about an ex-partner while travelling on a bus and gazing out the window. Or lying in bed and thinking about what it might be like to go on a holiday overseas.

If you were driving the bus or making the bed and your thoughts diverted from the primary task, this would be classed as mind wandering.

The benefits of mind wandering

Mind wandering is believed to play an important role in generating new ideas , conclusions or insights (also known as “aha! moments”). This is because it can give your mind a break and free it up to think more creatively.

This type of creativity does not always have to be related to creative pursuits (such as writing a song or making an artwork). It could include a new way to approach a university or school assignment or a project at work. Another benefit of mind wandering is relief from boredom, providing the opportunity to mentally retreat from a monotonous task.

For example, someone who does not enjoy washing dishes could think about their upcoming weekend plans while doing the chore. In this instance, mind wandering assists in “passing the time” during an uninteresting task.

Mind wandering also tends to be future-oriented. This can provide an opportunity to reflect upon and plan future goals, big or small. For example, what steps do I need to take to get a job after graduation? Or, what am I going to make for dinner tomorrow?

Read more: Alpha, beta, theta: what are brain states and brain waves? And can we control them?

What are the risks?

Mind wandering is not always beneficial, however. It can mean you miss out on crucial information. For example, there could be disruptions in learning if a student engages in mind wandering during a lesson that covers exam details. Or an important building block for learning.

Some tasks also require a lot of concentration in order to be safe. If you’re thinking about a recent argument with a partner while driving, you run the risk of having an accident.

That being said, it can be more difficult for some people to control their mind wandering. For example, mind wandering is more prevalent in people with ADHD.

Read more: How your brain decides what to think

What can you do to maximise the benefits?

There are several things you can do to maximise the benefits of mind wandering.

- be aware : awareness of mind wandering allows you to take note of and make use of any productive thoughts. Alternatively, if it is not a good time to mind wander it can help bring your attention back to the task at hand

context matters : try to keep mind wandering to non-demanding tasks rather than demanding tasks. Otherwise, mind wandering could be unproductive or unsafe. For example, try think about that big presentation during a car wash rather than when driving to and from the car wash

content matters : if possible, try to keep the content positive. Research has found , keeping your thoughts more positive, specific and concrete (and less about “you”), is associated with better wellbeing. For example, thinking about tasks to meet upcoming work deadlines could be more productive than ruminating about how you felt stressed or failed to meet past deadlines.

- Consciousness

- Daydreaming

- Concentration

- Mind wandering

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Regional Engagement Officer - Shepparton

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Mind & Body Articles & More

How mind-wandering may be good for you, new research suggests that mind-wandering can serve important functions for our performance and well-being..

When writing a song or a piece of prose, I often choose to let my mind wander, hoping the muse will strike. If it does, it not only moves my work along but feels great, too!

That’s why I was troubled by studies that found an association between mind-wandering and problems like unhappiness and depression —and even a shorter life expectancy . This research suggests that focusing one’s thoughts on the present moment is linked to well-being, while spacing out—which I personally love to do—is not.

Now, new studies are bringing nuance to this science. Whether or not mind-wandering is a negative depends on a lot of factors—like whether it’s purposeful or spontaneous, the content of your musings, and what kind of mood you are in. In some cases, a wandering mind can lead to creativity, better moods, greater productivity, and more concrete goals.

Here is what some recent research says about the upsides of a meandering mind.

Mind-wandering can make you more creative

It’s probably not a big surprise that mind-wandering augments creativity—particularly “divergent thinking,” or being able to come up with novel ideas.

In one study , researchers gave participants a creativity test called the Unusual Uses Task that asks you to dream up novel uses for an everyday item, like a paperclip or a newspaper. Between the first and second stages, participants either engaged in an undemanding task to encourage mind-wandering or a demanding task that took all of their concentration; or they were given a resting period or no rest. Those participants who engaged in mind-wandering during the undemanding task improved their performance much more than any of the other groups. Taking their focus off of the task and mind-wandering, instead, were critical to success.

“The findings reported here provide arguably the most direct evidence to date that conditions that favor mind-wandering also enhance creativity,” write the authors. In fact, they add, mind-wandering may “serve as a foundation for creative inspiration.”

As a more recent study found, mind-wandering improved people’s creativity above and beyond the positive effects of their reading ability or fluid intelligence, the general ability to solve problems or puzzles.

Mind-wandering seems to involve the default network of the brain, which is known to be active when we are not engaged directly in tasks and is also related to creativity.

So perhaps I’m right to let my focus wander while writing: It helps my mind put together information in novel and potentially compelling ways without my realizing it. It’s no wonder that my best inspirations seem to come when I’m in the shower or hiking for miles on end.

Mind-wandering can make you happier…depending on the content

The relationship between mind-wandering and mood may be more complicated than we thought.