10 Economic impacts of tourism + explanations + examples

Disclaimer: Some posts on Tourism Teacher may contain affiliate links. If you appreciate this content, you can show your support by making a purchase through these links or by buying me a coffee . Thank you for your support!

There are many economic impacts of tourism, and it is important that we understand what they are and how we can maximise the positive economic impacts of tourism and minimise the negative economic impacts of tourism.

Many argue that the tourism industry is the largest industry in the world. While its actual value is difficult to accurately determine, the economic potential of the tourism industry is indisputable. In fact, it is because of the positive economic impacts that most destinations embark on their tourism journey.

There is, however, more than meets the eye in most cases. The positive economic impacts of tourism are often not as significant as anticipated. Furthermore, tourism activity tends to bring with it unwanted and often unexpected negative economic impacts of tourism.

In this article I will discuss the importance of understanding the economic impacts of tourism and what the economic impacts of tourism might be. A range of positive and negative impacts are discussed and case studies are provided.

At the end of the post I have provided some additional reading on the economic impacts of tourism for tourism stakeholders , students and those who are interested in learning more.

Foreign exchange earnings

Contribution to government revenues, employment generation, contribution to local economies, development of the private sector, infrastructure cost, increase in prices, economic dependence of the local community on tourism, foreign ownership and management, economic impacts of tourism: conclusion, further reading on the economic impacts of tourism, the economic impacts of tourism: why governments invest.

Tourism brings with it huge economic potential for a destination that wishes to develop their tourism industry. Employment, currency exchange, imports and taxes are just a few of the ways that tourism can bring money into a destination.

In recent years, tourism numbers have increased globally at exponential rates, as shown in the World Tourism Organisation data below.

There are a number of reasons for this growth including improvements in technology, increases in disposable income, the growth of budget airlines and consumer desires to travel further, to new destinations and more often.

Here are a few facts about the economic importance of the tourism industry globally:

- The tourism economy represents 5 percent of world GDP

- Tourism contributes to 6-7 percent of total employment

- International tourism ranks fourth (after fuels, chemicals and automotive products) in global exports

- The tourism industry is valued at US$1trillion a year

- Tourism accounts for 30 percent of the world’s exports of commercial services

- Tourism accounts for 6 percent of total exports

- 1.4billion international tourists were recorded in 2018 (UNWTO)

- In over 150 countries, tourism is one of five top export earners

- Tourism is the main source of foreign exchange for one-third of developing countries and one-half of less economically developed countries (LEDCs)

There is a wealth of data about the economic value of tourism worldwide, with lots of handy graphs and charts in the United Nations Economic Impact Report .

In short, tourism is an example of an economic policy pursued by governments because:

- it brings in foreign exchange

- it generates employment

- it creates economic activity

Building and developing a tourism industry, however, involves a lot of initial and ongoing expenditure. The airport may need expanding. The beaches need to be regularly cleaned. New roads may need to be built. All of this takes money, which is usually a financial outlay required by the Government.

For governments, decisions have to be made regarding their expenditure. They must ask questions such as:

How much money should be spent on the provision of social services such as health, education, housing?

How much should be spent on building new tourism facilities or maintaining existing ones?

If financial investment and resources are provided for tourism, the issue of opportunity costs arises.

By opportunity costs, I mean that by spending money on tourism, money will not be spent somewhere else. Think of it like this- we all have a specified amount of money and when it runs out, it runs out. If we decide to buy the new shoes instead of going out for dinner than we might look great, but have nowhere to go…!

In tourism, this means that the money and resources that are used for one purpose may not then be available to be used for other purposes. Some destinations have been known to spend more money on tourism than on providing education or healthcare for the people who live there, for example.

This can be said for other stakeholders of the tourism industry too.

There are a number of independent, franchised or multinational investors who play an important role in the industry. They may own hotels, roads or land amongst other aspects that are important players in the overall success of the tourism industry. Many businesses and individuals will take out loans to help fund their initial ventures.

So investing in tourism is big business, that much is clear. What what are the positive and negative impacts of this?

Positive economic impacts of tourism

So what are the positive economic impacts of tourism? As I explained, most destinations choose to invest their time and money into tourism because of the positive economic impacts that they hope to achieve. There are a range of possible positive economic impacts. I will explain the most common economic benefits of tourism below.

One of the biggest benefits of tourism is the ability to make money through foreign exchange earnings.

Tourism expenditures generate income to the host economy. The money that the country makes from tourism can then be reinvested in the economy. How a destination manages their finances differs around the world; some destinations may spend this money on growing their tourism industry further, some may spend this money on public services such as education or healthcare and some destinations suffer extreme corruption so nobody really knows where the money ends up!

Some currencies are worth more than others and so some countries will target tourists from particular areas. I remember when I visited Goa and somebody helped to carry my luggage at the airport. I wanted to give them a small tip and handed them some Rupees only to be told that the young man would prefer a British Pound!

Currencies that are strong are generally the most desirable currencies. This typically includes the British Pound, American, Australian and Singapore Dollar and the Euro .

Tourism is one of the top five export categories for as many as 83% of countries and is a main source of foreign exchange earnings for at least 38% of countries.

Tourism can help to raise money that it then invested elsewhere by the Government. There are two main ways that this money is accumulated.

Direct contributions are generated by taxes on incomes from tourism employment and tourism businesses and things such as departure taxes.

Taxes differ considerably between destinations. I will never forget the first time that I was asked to pay a departure tax (I had never heard of it before then), because I was on my way home from a six month backpacking trip and I was almost out of money!

Japan is known for its high departure taxes. Here is a video by a travel blogger explaining how it works.

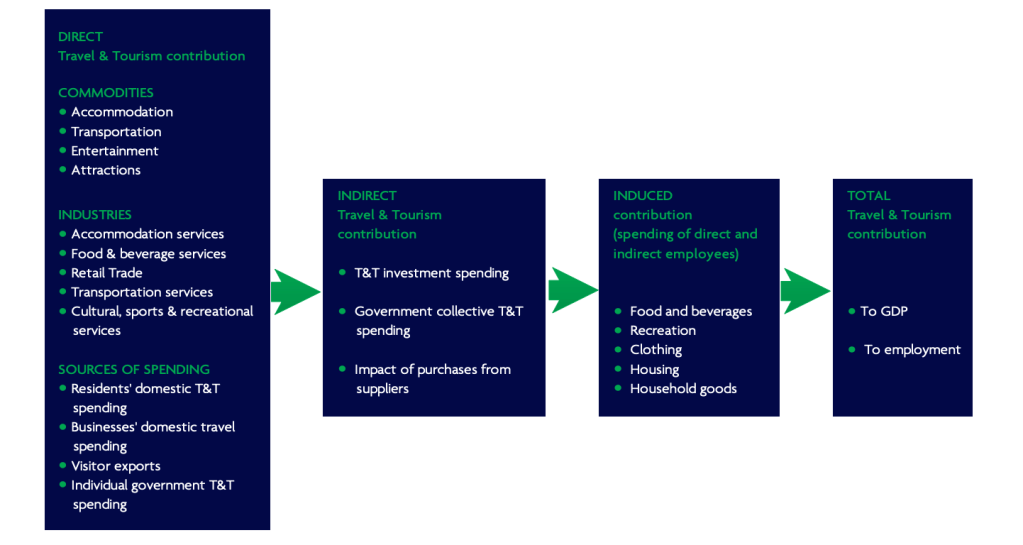

According to the World Tourism Organisation, the direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2018 was $2,750.7billion (3.2% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 3.6% to $2,849.2billion in 2019.

Indirect contributions come from goods and services supplied to tourists which are not directly related to the tourism industry.

Take food, for example. A tourist may buy food at a local supermarket. The supermarket is not directly associated with tourism, but if it wasn’t for tourism its revenues wouldn’t be as high because the tourists would not shop there.

There is also the income that is generated through induced contributions . This accounts for money spent by the people who are employed in the tourism industry. This might include costs for housing, food, clothing and leisure Activities amongst others. This will all contribute to an increase in economic activity in the area where tourism is being developed.

The rapid expansion of international tourism has led to significant employment creation. From hotel managers to theme park operatives to cleaners, tourism creates many employment opportunities. Tourism supports some 7% of the world’s workers.

There are two types of employment in the tourism industry: direct and indirect.

Direct employment includes jobs that are immediately associated with the tourism industry. This might include hotel staff, restaurant staff or taxi drivers, to name a few.

Indirect employment includes jobs which are not technically based in the tourism industry, but are related to the tourism industry. Take a fisherman, for example. He does not have any contact of dealings with tourists. BUT he does sell his fish to the hotel which serves tourists. So he is indirectly employed by the tourism industry, because without the tourists he would not be supplying the fish to the hotel.

It is because of these indirect relationships, that it is very difficult to accurately measure the economic value of tourism.

It is also difficult to say how many people are employed, directly and indirectly, within the tourism industry.

Furthermore, many informal employments may not be officially accounted for. Think tut tut driver in Cambodia or street seller in The Gambia – these people are not likely to be registered by the state and therefore their earnings are not declared.

It is for this reason that some suggest that the actual economic benefits of tourism may be as high as double that of the recorded figures!

All of the money raised, whether through formal or informal means, has the potential to contribute to the local economy.

If sustainable tourism is demonstrated, money will be directed to areas that will benefit the local community most.

There may be pro-poor tourism initiatives (tourism which is intended to help the poor) or volunteer tourism projects.

The government may reinvest money towards public services and money earned by tourism employees will be spent in the local community. This is known as the multiplier effect.

The multiplier effect relates to spending in one place creating economic benefits elsewhere. Tourism can do wonders for a destination in areas that may seem to be completely unrelated to tourism, but which are actually connected somewhere in the economic system.

Let me give you an example.

A tourist buys an omelet and a glass of orange juice for their breakfast in the restaurant of their hotel. This simple transaction actually has a significant multiplier effect. Below I have listed just a few of the effects of the tourist buying this breakfast.

The waiter is paid a salary- he spends his salary on schooling for his kids- the school has more money to spend on equipment- the standard of education at the school increases- the kids graduate with better qualifications- as adults, they secure better paying jobs- they can then spend more money in the local community…

The restaurant purchases eggs from a local farmer- the farmer uses that money to buy some more chickens- the chicken breeder uses that money to improve the standards of their cages, meaning that the chickens are healthier, live longer and lay more eggs- they can now sell the chickens for a higher price- the increased money made means that they can hire an extra employee- the employee spends his income in the local community…

The restaurant purchase the oranges from a local supplier- the supplier uses this money to pay the lorry driver who transports the oranges- the lorry driver pays road tax- the Government uses said road tax income to fix pot holes in the road- the improved roads make journeys quicker for the local community…

So as you can see, that breakfast that the tourist probably gave not another thought to after taking his last mouthful of egg, actually had the potential to have a significant economic impact on the local community!

The private sector has continuously developed within the tourism industry and owning a business within the private sector can be extremely profitable; making this a positive economic impact of tourism.

Whilst many businesses that you will come across are multinational, internationally-owned organisations (which contribute towards economic leakage ).

Many are also owned by the local community. This is the case even more so in recent years due to the rise in the popularity of the sharing economy and the likes of Airbnb and Uber, which encourage the growth of businesses within the local community.

Every destination is different with regards to how they manage the development of the private sector in tourism.

Some destinations do not allow multinational organisations for fear that they will steal business and thus profits away from local people. I have seen this myself in Italy when I was in search of a Starbucks mug for my collection , only to find that Italy has not allowed the company to open up any shops in their country because they are very proud of their individually-owned coffee shops.

Negative economic impacts of tourism

Unfortunately, the tourism industry doesn’t always smell of roses and there are also several negative economic impacts of tourism.

There are many hidden costs to tourism, which can have unfavourable economic effects on the host community.

Whilst such negative impacts are well documented in the tourism literature, many tourists are unaware of the negative effects that their actions may cause. Likewise, many destinations who are inexperienced or uneducated in tourism and economics may not be aware of the problems that can occur if tourism is not management properly.

Below, I will outline the most prominent negative economic impacts of tourism.

Economic leakage in tourism is one of the major negative economic impacts of tourism. This is when money spent does not remain in the country but ends up elsewhere; therefore limiting the economic benefits of tourism to the host destination.

The biggest culprits of economic leakage are multinational and internationally-owned corporations, all-inclusive holidays and enclave tourism.

I have written a detailed post on the concept of economic leakage in tourism, you can take a look here- Economic leakage in tourism explained .

Another one of the negative economic impacts of tourism is the cost of infrastructure. Tourism development can cost the local government and local taxpayers a great deal of money.

Tourism may require the government to improve the airport, roads and other infrastructure, which are costly. The development of the third runway at London Heathrow, for example, is estimated to cost £18.6billion!

Money spent in these areas may reduce government money needed in other critical areas such as education and health, as I outlined previously in my discussion on opportunity costs.

One of the most obvious economic impacts of tourism is that the very presence of tourism increases prices in the local area.

Have you ever tried to buy a can of Coke in the supermarket in your hotel? Or the bar on the beachfront? Walk five minutes down the road and try buying that same can in a local shop- I promise you, in the majority of cases you will see a BIG difference In cost! (For more travel hacks like this subscribe to my newsletter – I send out lots of tips, tricks and coupons!)

Increasing demand for basic services and goods from tourists will often cause price hikes that negatively impact local residents whose income does not increase proportionately.

Tourism development and the related rise in real estate demand may dramatically increase building costs and land values. This often means that local people will be forced to move away from the area that tourism is located, known as gentrification.

Taking measures to ensure that tourism is managed sustainably can help to mitigate this negative economic impact of tourism. Techniques such as employing only local people, limiting the number of all-inclusive hotels and encouraging the purchasing of local products and services can all help.

Another one of the major economic impacts of tourism is dependency. Many countries run the risk of becoming too dependant on tourism. The country sees $ signs and places all of its efforts in tourism. Whilst this can work out well, it is also risky business!

If for some reason tourism begins to lack in a destination, then it is important that the destination has alternative methods of making money. If they don’t, then they run the risk of being in severe financial difficulty if there is a decline in their tourism industry.

In The Gambia, for instance, 30% of the workforce depends directly or indirectly on tourism. In small island developing states, percentages can range from 83% in the Maldives to 21% in the Seychelles and 34% in Jamaica.

There are a number of reasons that tourism could decline in a destination.

The Gambia has experienced this just recently when they had a double hit on their tourism industry. The first hit was due to political instability in the country, which has put many tourists off visiting, and the second was when airline Monarch went bust, as they had a large market share in flights to The Gambia.

Other issues that could result in a decline in tourism includes economic recession, natural disasters and changing tourism patterns. Over-reliance on tourism carries risks to tourism-dependent economies, which can have devastating consequences.

The last of the negative economic impacts of tourism that I will discuss is that of foreign ownership and management.

As enterprise in the developed world becomes increasingly expensive, many businesses choose to go abroad. Whilst this may save the business money, it is usually not so beneficial for the economy of the host destination.

Foreign companies often bring with them their own staff, thus limiting the economic impact of increased employment. They will usually also export a large proportion of their income to the country where they are based. You can read more on this in my post on economic leakage in tourism .

As I have demonstrated in this post, tourism is a significant economic driver the world over. However, not all economic impacts of tourism are positive. In order to ensure that the economic impacts of tourism are maximised, careful management of the tourism industry is required.

If you enjoyed this article on the economic impacts of tourism I am sure that you will love these too-

- Environmental impacts of tourism

- The 3 types of travel and tourism organisations

- 150 types of tourism! The ultimate tourism glossary

- 50 fascinating facts about the travel and tourism industry

- 23 Types of Water Transport To Keep You Afloat

Liked this article? Click to share!

What is overtourism and how can we overcome it?

The issue of overtourism has become a major concern due to the surge in travel following the pandemic. Image: Reuters/Manuel Silvestri (ITALY - Tags: ENTERTAINMENT)

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joseph Martin Cheer

Marina novelli.

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Travel and Tourism is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, travel and tourism.

Listen to the article

- Overtourism has once again become a concern, particularly after the rebound of international travel post-pandemic.

- Communities in popular destinations worldwide have expressed concerns over excess tourism on their doorstep.

- Here we outline the complexities of overtourism and the possible measures that can be taken to address the problem.

The term ‘overtourism’ has re-emerged as tourism recovery has surged around the globe. But already in 2019, angst over excessive tourism growth was so high that the UN World Tourism Organization called for “such growth to be managed responsibly so as to best seize the opportunities tourism can generate for communities around the world”.

This was especially evident in cities like Barcelona, where anti-tourism sentiment built up in response to pent-up frustration about rapid and unyielding tourism growth. Similar local frustration emerged in other famous cities, including Amsterdam , Venice , London , Kyoto and Dubrovnik .

While the pandemic was expected to usher in a new normal where responsible and sustainable travel would emerge, this shift was evidently short-lived, as demand surged in 2022 and 2023 after travel restrictions eased.

Have you read?

Ten principles for sustainable destinations: charting a new path forward for travel and tourism.

This has been witnessed over the recent Northern Hemisphere summer season, during which popular destinations heaved under the pressure of pent-up post-pandemic demand , with grassroots communities articulating over-tourism concerns.

Concerns over excess tourism have not only been seen in popular cities but also on the islands of Hawaii and Greece , beaches in Spain , national parks in the United States and Africa , and places off the beaten track like Japan ’s less explored regions.

What is overtourism?

The term overtourism was employed by Freya Petersen in 2001, who lamented the excesses of tourism development and governance deficits in the city of Pompei. Her sentiments are increasingly familiar among tourists in other top tourism destinations more than 20 years later.

Overtourism is more than a journalistic device to arouse host community anxiety or demonize tourists through anti-tourism activism. It is also more than simply being a question of management – although poor or lax governance most definitely accentuates the problem.

Governments at all levels must be decisive and firm about policy responses that control the nature of tourist demand and not merely give in to profits that flow from tourist expenditure and investment.

Overtourism is often oversimplified as being a problem of too many tourists. While that may well be an underlying symptom of excess, it fails to acknowledge the myriad factors at play.

In its simplest iteration, overtourism results from tourist demand exceeding the carrying capacity of host communities in a destination. Too often, the tourism supply chain stimulates demand, giving little thought to the capacity of destinations and the ripple effects on the well-being of local communities.

Overtourism is arguably a social phenomenon too. In China and India, two of the most populated countries where space is a premium, crowded places are socially accepted and overtourism concerns are rarely articulated, if at all. This suggests that cultural expectations of personal space and expectations of exclusivity differ.

We also tend not to associate ‘overtourism’ with Africa . But uncontrolled growth in tourist numbers is unsustainable anywhere, whether in an ancient European city or the savannah of a sub-Saharan context.

Overtourism must also have cultural drivers that are intensified when tourists' culture is at odds with that of host communities – this might manifest as breaching of public norms, irritating habits, unacceptable behaviours , place-based displacement and inconsiderate occupation of space.

The issue also comes about when the economic drivers of tourism mean that those who stand to benefit from growth are instead those who pay the price of it, particularly where gentrification and capital accumulation driven from outside results in local resident displacement and marginalization.

Overcoming overtourism excesses

Radical policy measures that break the overtourism cycle are becoming more common. For example, Amsterdam has moved to ban cruise ships by closing the city’s cruise terminal.

Tourism degrowth has long been posited as a remedy to overtourism. While simply cutting back on tourist numbers seems like a logical response, whether the economic trade-offs of fewer tourists will be tolerated is another thing altogether.

The Spanish island of Lanzarote moved to desaturate the island by calling the industry to focus on quality tourism rather than quantity. This shift to quality, or higher yielding, tourists has been mirrored in many other destinations, like Bali , for example.

Dispersing tourists outside hotspots is commonly seen as a means of dealing with too much tourism. However, whether sufficient interest to go off the beaten track can be stimulated might be an immoveable constraint, or simply result in problem shifting .

Demarketing destinations has been applied with varying degrees of success. However, whether it can address the underlying factors in the long run is questioned, particularly as social media influencers and travel writers continue to give attention to touristic hotspots. In France, asking visitors to avoid Mont Saint-Michelle and instead recommending they go elsewhere is evidence of this.

Introducing entry fees and gates to over-tourist places like Venice is another deterrent. This assumes visitors won’t object to paying and that revenues generated are spent on finding solutions rather than getting lost in authorities’ consolidated revenue.

Advocacy and awareness campaigns against overtourism have also been prominent, but whether appeals to tourists asking them to curb irresponsible behaviours have had any impact remains questionable as incidents continue —for example, the Palau Pledge and New Zealand’s Tiaki Promise appeal for more responsible behaviours.

Curtailing the use of the word overtourism is also posited – in the interest of avoiding the rise of moral panics and the swell of anti-tourism social movements, but pretending the phenomenon does not exist, or dwelling on semantics won’t solve the problem .

Solutions to address overtourism

The solutions to dealing adequately with the effects of overtourism are likely to be many and varied and must be tailored to the unique, relevant destination .

The tourism supply chain must also bear its fair share of responsibility. While popular destinations are understandably an easier sell, redirecting tourism beyond popular honeypots like urban heritage sites or overcrowded beaches needs greater impetus to avoid shifting the problem elsewhere.

Local authorities must exercise policy measures that establish capacity limits, then ensure they are upheld, and if not, be held responsible for their inaction .

Meanwhile, tourists themselves should take responsibility for their behaviour and decisions while travelling, as this can make a big difference to the impact on local residents .

Those investing in tourism should support initiatives that elevate local priorities and needs, and not simply exercise a model of maximum extraction for shareholders in the supply chain.

How is the World Economic Forum supporting the development of cities and communities globally?

The Data for the City of Tomorrow report highlighted that in 2023, around 56% of the world is urbanized. Almost 65% of people use the internet. Soon, 75% of the world’s jobs will require digital skills.

The World Economic Forum’s Centre for Urban Transformation is at the forefront of advancing public-private collaboration in cities. It enables more resilient and future-ready communities and local economies through green initiatives and the ethical use of data.

Learn more about our impact:

- Net Zero Carbon Cities: Through this initiative, we are sharing more than 200 leading practices to promote sustainability and reducing emissions in urban settings and empower cities to take bold action towards achieving carbon neutrality .

- G20 Global Smart Cities Alliance: We are dedicated to establishing norms and policy standards for the safe and ethical use of data in smart cities , leading smart city governance initiatives in more than 36 cities around the world.

- Empowering Brazilian SMEs with IoT adoption : We are removing barriers to IoT adoption for small and medium-sized enterprises in Brazil – with participating companies seeing a 192% return on investment.

- IoT security: Our Council on the Connected World established IoT security requirements for consumer-facing devices . It engages over 100 organizations to safeguard consumers against cyber threats.

- Healthy Cities and Communities: Through partnerships in Jersey City and Austin, USA, as well as Mumbai, India, this initiative focuses on enhancing citizens' lives by promoting better nutritional choices, physical activity, and sanitation practices.

Want to know more about our centre’s impact or get involved? Contact us .

National tourist offices and destination management organizations must support development that is nuanced and in tune with the local backdrop rather than simply mimicking mass-produced products and experiences.

The way tourist experiences are developed and shaped must be transformed to move away from outright consumerist fantasies to responsible consumption .

The overtourism problem will be solved through a clear-headed, collaborative and case-specific assessment of the many drivers in action. Finally, ignoring historical precedents that have led to the current predicament of overtourism and pinning this on oversimplified prescriptions abandons any chance of more sustainable and equitable tourism futures .

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Travel and Tourism .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How Japan is attracting digital nomads to shape local economies and innovation

Naoko Tochibayashi and Naoko Kutty

March 28, 2024

Turning tourism into development: Mitigating risks and leveraging heritage assets

Abeer Al Akel and Maimunah Mohd Sharif

February 15, 2024

Buses are key to fuelling Indian women's economic success. Here's why

Priya Singh

February 8, 2024

These are the world’s most powerful passports to have in 2024

Thea de Gallier

January 31, 2024

These are the world’s 9 most powerful passports in 2024

South Korea is launching a special visa for K-pop lovers

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

- INTELLIGENT TRAVEL

Is Tourism Destroying the World?

Travel is transforming the world, and not always for the better. Though it’s an uncomfortable reality (who doesn’t like to travel?), it’s something award-winning journalist Elizabeth Becker devoted five years of her life to investigating. The result is Overbooked: The Exploding Business of Travel and Tourism .

I caught up with the author to get the inside scoop on the book, what prompted her to write it, and what she learned along the way, and this is what she had to say.

Leslie Trew Magraw: You made a name for yourself as a war correspondent covering Cambodia for The Washington Post . What prompted you to write this book?

Elizabeth Becker: My profession has been to understand world events. I reported from Asia and Europe [for the Post ] and later was the senior foreign editor at NPR. At The New York Times , I became the international economics correspondent in 2002, and that is when I began noticing the explosion of tourism and how much countries rich and poor were coming to rely on it.

But tourism isn’t treated as a serious business or economic force. Travel sections are all about the best vacations. So I used a fellowship at Harvard to begin my research and then wrote this book to point out what seemed so obvious: Tourism is among the biggest global industries and, as such, has tremendous impacts—environmental, cultural, economic—that have to be acknowledged and addressed.

Which country can you point to as a model for sustainable tourism?

One of the more ambitious is France , which is aiming for sustainability in the whole country. The key, I think, is that the French never fully bought in to the modern obsession with tourist overdevelopment. They have been nurturing their own culture and landscape, cities, and villages for decades. Since they have tied their economy to tourism, they have applied a precise and country-wide approach that mostly works.

All relevant ministries are involved, including culture, commerce, agriculture, sports, and transportation. Planning is bottom up, beginning with locals at destinations who decide what they want to promote and how they want to improve. The French obsession with protecting their culture—some would call it arrogance—has worked in their favor. The planning and bureaucracy required to make this work would try the patience of many governments.

Now, even though the country is smaller than the state of Texas, France is the most popular destination in the world. Tourism officials told me one of their biggest worries is becoming victims of their success: too many foreigners buying second homes or retirement homes in French villages and Parisian neighborhoods, which could tip the balance and undermine that sustainable and widely admired French way of life.

Many destinations are making impressive changes. Philanthropists are helping African game parks find their footing. I was lucky to see how Paul Allen , for instance, is helping in Zambia .

Which country is doing it all wrong?

Cambodia has made some bad choices in tourism. It is blessed with the magnificent temples of Angkor , glorious beaches in the south, cities with charming overlay of the French colonial heritage, and a rural landscape of sugar palms, rice paddies, and houses on stilts.

Yet, rather than protect these gems, the government has allowed rapacious tourism to threaten the very attractions that bring tourists. Tourism is seen as a cash cow.

Some of the capital’s most stunning historic buildings are being razed to build look-alike modern hotels. In Angkor, a thicket of new hotels has outpaced infrastructure and is draining the water table so badly the temples are sinking—and profits from tourism do not reach the common people, who are now among the poorest in the country.

In addition, Cambodia has become synonymous with sex tourism that exploits young girls and boys. The latest wrinkle is to encourage tourists on the “genocide trail” to see the killing fields and execution centers from the Khmer Rouge era.

With more than a billion people traveling each year, how can we see the world without destroying it?

That is the essential question. Countries are figuring out how to protect their destinations in quiet, non-offensive ways. They control the number of hotel beds, the number of flights to and from a country, the number of tour buses allowed. Some have “sacrifice zones,” where tourists are allowed to flood one section of beachfront, for example, while the rest is protected as a wildlife preserve or [reserved] for locals. Most countries are heavily promoting off-season travel as the most obvious way to control crowds.

Countries are also putting more muscle into regulations [governing] pollution. The toughest problem is breaking the habit of politicians being too close to the industry to the detriment of their country. Money talks in tourism as in any other big business. Luxury chains wanting a store near a major tourist attraction will pay high rents to push out locals. Officials fail to enforce rules against phony “authentic” souvenirs.

One of the worst offenders are the supersize cruise ships that swarm localities, straining local services and sites and giving back little in return.

What do you think will be the biggest challenge for 21st-century travelers?

Avoiding “drive-by tourism.” This is a phrase coined by Paul Bennett of Context Travel , referring to the growing habit of people visiting a destination for a few hours—maybe a few days—and seeing only a blur of sights with little appreciation for the country, culture, or people.

One of the eureka moments in my five years of research was reading old guidebooks in the Library of Congress.

The Baedeker Guides were written in consultation with historians and archaeologists who presumed the tourists wanted to immerse themselves in a country. They included a short dictionary of the language of the country and, only at the very end, short lists of hotels and restaurants.

Today it is the reverse: Guides have short paragraphs about history, culture, and politics and long lists of where to eat and sleep.

- Nat Geo Expeditions

My advice is to first be a tourist where you live. Explore the museums, the farms, the churches, the night life, the historic monuments—and then read up on local politics and history.

If you’re interested in volunteering overseas, first volunteer at home. Then when you’re planning your next trip abroad, use that experience as a template and study up on the destination you’re about to visit.

Don’t forget to try to learn something of the local language. It is a gift.

Q: Are there any tourism trends that give you hope for the future of travel?

A: People are again recognizing that travel is a privilege. Responsible tourism in its various forms—volunteer tourism, adventure tourism, slow tourism (where people take their time), agro-tourism (where visitors live and work on a farm), ecotourism , geotourism—all speak to tourists’ desire to respect the places they visit and the people they meet. I think people are also recognizing that bargain travel has hidden expenses and dangers.

Costa Rica was an eye-opener for me; it deserves its reputation as a leader in responsible tourism that nurtures nature and society.

Finally, several groups including the United Nations World Tourism Organization have put together a global sustainable tourism council with a certification program to show tourists which places are genuinely making the effort.

Thoughts? Counterpoints? Leave a comment to let us know how you feel about this important topic.

Related Topics

- PEOPLE AND CULTURE

FREE BONUS ISSUE

- Perpetual Planet

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Photography

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Gory Details

- 2023 in Review

- Best of the World

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

The COVID-19 travel shock hit tourism-dependent economies hard

- Download the paper here

Subscribe to the Hutchins Roundup and Newsletter

Gian maria milesi-ferretti gian maria milesi-ferretti senior fellow - economic studies , the hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy.

August 12, 2021

The COVID crisis has led to a collapse in international travel. According to the World Tourism Organization , international tourist arrivals declined globally by 73 percent in 2020, with 1 billion fewer travelers compared to 2019, putting in jeopardy between 100 and 120 million direct tourism jobs. This has led to massive losses in international revenues for tourism-dependent economies: specifically, a collapse in exports of travel services (money spent by nonresident visitors in a country) and a decline in exports of transport services (such as airline revenues from tickets sold to nonresidents).

This “travel shock” is continuing in 2021, as restrictions to international travel persist—tourist arrivals for January-May 2021 are down a further 65 percent from the same period in 2020, and there is substantial uncertainty on the nature and timing of a tourism recovery.

We study the economic impact of the international travel shock during 2020, particularly the severity of the hit to countries very dependent on tourism. Our main result is that on a cross-country basis, the share of tourism activities in GDP is the single most important predictor of the growth shortfall in 2020 triggered by the COVID-19 crisis (relative to pre-pandemic IMF forecasts), even when compared to measures of the severity of the pandemic. For instance, Grenada and Macao had very few recorded COVID cases in relation to their population size and no COVID-related deaths in 2020—yet their GDP contracted by 13 percent and 56 percent, respectively.

International tourism destinations and tourism sources

Countries that rely heavily on tourism, and in particular international travelers, tend to be small, have GDP per capita in the middle-income and high-income range, and are preponderately net debtors. Many are small island economies—Jamaica and St. Lucia in the Caribbean, Cyprus and Malta in the Mediterranean, the Maldives and Seychelles in the Indian Ocean, or Fiji and Samoa in the Pacific. Prior to the COVID pandemic, median annual net revenues from international tourism (spending by foreign tourists in the country minus tourism spending by domestic residents overseas) in these island economies were about one quarter of GDP, with peaks around 50 percent of GDP, such as Aruba and the Maldives.

But there are larger economies heavily reliant on international tourism. For instance, in Croatia average net international tourism revenues from 2015-2019 exceeded 15 percent of GDP, 8 percent in the Dominican Republic and Thailand, 7 percent in Greece, and 5 percent in Portugal. The most extreme example is Macao, where net revenues from international travel and tourism were around 68 percent of GDP during 2015-19. Even in dollar terms, Macao’s net revenues from tourism were the fourth highest in the world, after the U.S., Spain, and Thailand.

In contrast, for countries that are net importers of travel and tourism services—that is, countries whose residents travel widely abroad relative to foreign travelers visiting the country—the importance of such spending is generally much smaller as a share of GDP. In absolute terms, the largest importer of travel services is China (over $200 billion, or 1.7 percent of GDP on average during 2015-19), followed by Germany and Russia. The GDP impact for these economies of a sharp reduction in tourism outlays overseas is hence relatively contained, but it can have very large implications on the smaller economies their tourists travel to—a prime example being Macao for Chinese travelers.

How did tourism-dependent economies cope with the disappearance of a large share of their international revenues in 2020? They were forced to borrow more from abroad (technically, their current account deficit widened, or their surplus shrank), but also reduced net international spending in other categories. Imports of goods declined (reflecting both a contraction in domestic demand and a decline in tourism inputs such as imported food and energy) and payments to foreign creditors were lower, reflecting the decline in returns for foreign-owned hotel infrastructure.

The growth shock

We then examine whether countries more dependent on tourism suffered a bigger shock to economic activity in 2020 than other countries, measuring this shock as the difference between growth outcomes in 2020 and IMF growth forecasts as of January 2020, just prior to the pandemic. Our measure of the overall importance of tourism is the share of GDP accounted for by tourism-related activity over the 5 years preceding the pandemic, assembled by the World Travel and Tourism Council and disseminated by the World Bank . This measure takes into account the importance of domestic tourism as well as international tourism.

Among the 40 countries with the largest share of tourism in GDP, the median size of growth shortfall compared to pre-COVID projections was around 11 percent, as against 6 percent for countries less dependent on tourism. For instance, in the tourism-dependent group, Greece, which was expected to grow by 2.3 percent in 2020, shrunk by over 8 percent, while in the other group, Germany, which was expected to grow by around 1 percent, shrunk by 4.8 percent. The scatter plot of Figure 2 provides more striking visual evidence of a negative correlation (-0.72) between tourism dependence and the growth shock in 2020.

Of course, many other factors may have affected differences in performance across economies—for instance, the intensity of the pandemic as well as the stringency of the associated lockdowns. We therefore build a simple statistical model that relates the “growth shock” in 2020 to these factors alongside our tourism variable, and also takes into account other potentially relevant country characteristics, such as the level of development, the composition of output, and country size. The message: the dependence on tourism is a key explanatory variable of the growth shock in 2020. For instance, the analysis suggests that going from the share of tourism in GDP of Canada (around 6 percent) to the one of Mexico (around 16 percent) would reduce growth in 2020 by around 2.5 percentage points. If we instead go from the tourism share of Canada to the one of Jamaica (where the share of tourism in GDP approaches one third), growth would be lower by over 6 percentage points.

Measures of the severity of the pandemic, the intensity of lockdowns, the level of development, and the sectoral composition of GDP (value added accounted for by manufacturing and agriculture) also matter, but quantitatively less so than tourism. And results are not driven by very small economies; tourism is still a key explanatory variable of the 2020 growth shock even if we restrict our sample to large economies. Among tourism-dependent economies, we also find evidence that those relying more heavily on international tourism experienced a more severe hit to economic activity when compared to those relying more on domestic tourism.

Given data availability at the time of writing, the evidence we provided is limited to 2020. The outlook for international tourism in 2021, if anything, is worse, though with increasing vaccine coverage the tide could turn next year. The crisis poses particularly daunting challenges to smaller tourist destinations, given limited possibilities for diversification. In many cases, particularly among emerging and developing economies, these challenges are compounded by high starting levels of domestic and external indebtedness, which can limit the space for an aggressive fiscal response. Helping these countries cope with the challenges posed by the pandemic and restoring viable public and external finances will require support from the international community.

Read the full paper here.

Related Content

February 18, 2021

Eldah Onsomu, Boaz Munga, Violet Nyabaro

July 28, 2021

Célia Belin

May 21, 2021

The author thanks Manuel Alcala Kovalski and Jimena Ruiz Castro for their excellent research assistance.

Economic Studies

The Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy

Janet Gornick, David Brady, Ive Marx, Zachary Parolin

April 17, 2024

Homi Kharas, Charlotte Rivard

April 16, 2024

Homi Kharas, Vera Songwe

April 15, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

A Year Without Travel

How Bad Was 2020 for Tourism? Look at the Numbers.

The dramatic effects of the coronavirus pandemic on the travel industry and beyond are made clear in six charts.

By Stephen Hiltner and Lalena Fisher

Numbers alone cannot capture the scope of the losses that have mounted in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Data sets are crude tools for plumbing the depth of human suffering , or the immensity of our collective grief .

But numbers can help us comprehend the scale of certain losses — particularly in the travel industry , which in 2020 experienced a staggering collapse.

Around the world, international arrivals are estimated to have dropped to 381 million in 2020, down from 1.461 billion in 2019 — a 74 percent decline . In countries whose economies are heavily reliant on tourism , the precipitous drop in visitors was, and remains, devastating.

According to recent figures from the United Nations World Tourism Organization, the decline in international travel in 2020 resulted in an estimated loss of $1.3 trillion in global export revenues. As the agency notes, this figure is more than 11 times the loss that occurred in 2009 as a result of the global economic crisis.

The following charts — which address changes in international arrivals, emissions, air travel, the cruise industry and car travel — offer a broad overview of the effects of the coronavirus pandemic within the travel industry and beyond.

International arrivals in tourism-dependent economies

Macau, a top gambling destination, is highly dependent on travelers, as measured by the share

of its G.D.P. that is generated by tourism. Its international visitor numbers plummeted in 2020:

ARRIVALS IN 2020

The following countries are also among the world’s most dependent on travel, in terms of both their

G.D.P. and their international tourism receipts as a percent of total exports:

U.S. Virgin Islands

The Bahamas

Antigua and Barbuda

Saint Lucia

Cook Islands

0.5 million

Macau, a gambling destination, is dependent on travelers,

as measured by the share of its G.D.P. that is generated by

tourism. Its international visitor numbers plummeted in 2020:

The following countries are also among the world’s most

dependent on travel, in terms of both their G.D.P. and their

international tourism receipts as a percent of total exports:

Before the pandemic, tourism accounted for one out of every 10 jobs around the world. In many places, though, travel plays an even greater role in the local economy.

Consider the Maldives, where in recent years international tourism has accounted for around two-thirds of the country’s G.D.P. , when considering direct and indirect contributions.

As lockdowns fell into place worldwide, international arrivals in the Maldives plunged; from April through September of 2020, they were down 97 percent compared to the same period in 2019. Throughout all of 2020, arrivals were down by more than 67 percent compared with 2019. (Arrival numbers slowly improved after the country reopened in July; the government, eager to promote tourism and mitigate losses, lured travelers with marketing campaigns and even courted influencers with paid junkets .)

Similar developments played out in places such as Macau, Aruba and the Bahamas: shutdowns in February and March, followed by incremental increases later in the year.

The economic effect of travel-related declines has been stunning. In Macau, for example, the G.D.P. contracted by more than 50 percent in 2020.

And the effects could be long-lasting; in some areas, travel is not expected to return to pre-pandemic levels until 2024.

Travelers passing through T.S.A. airport security checkpoints

The pandemic upended commercial aviation. One way to visualize the effect of lockdowns on air travel is to consider the number of passengers screened on a daily basis at Transportation Security Administration checkpoints.

Traveler screenings plunged in March before hitting a low point on April 14, when 87,534 passengers were screened — a 96 percent decline as compared with the same date in 2019.

Numbers have risen relatively steadily since then, though today the screening figures still sit at less than half of what they were a year earlier.

According to the International Air Transport Association, an airline trade group, global passenger traffic in 2020 fell by 65.9 percent as compared to 2019, the largest year-on-year decline in aviation history.

Daily carbon dioxide emissions from aviation

3.0 million metric tons

Another way to visualize the drop-off in air travel last year is to consider the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) emitted by aircraft around the world.

According to figures from Carbon Monitor , an international initiative that provides estimates of daily CO2 emissions, worldwide emissions from aviation fell by nearly 50 percent last year — to around 500 million metric tons of CO2, down from around 1 billion metric tons in 2019. (Those numbers are expected to rebound, though the timing will depend largely on how long corporate and international travel remain sidelined .)

All told, CO2 emissions from fossil fuels dropped by 2.6 billion metric tons in 2020, a 7 percent reduction from 2019, driven in large part by transportation declines.

Yearly revenues of three of the biggest cruise lines

$20 billion

ROYAL CARIBBEAN

Few industries played as central and public a role in the early months of the coronavirus pandemic as did the major cruise lines — beginning with the outbreak aboard the Diamond Princess .

In a scathing rebuke of the industry issued in July, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention blamed cruise companies for widespread transmission of the virus, pointing to 99 outbreaks aboard 123 cruise ships in U.S. waters alone.

While precise passenger data for 2020 is not yet available, the publicly disclosed revenues — which include ticket sales and onboard purchases — from three of the largest cruise lines offer a dramatic narrative: strong revenues in the early months of 2020, followed by a steep decline.

Third-quarter revenues for Carnival Corporation, the industry’s biggest player, showed a year-to-year decline of 99.5 percent — to $31 million in 2020, down from $6.5 billion in 2019.

The outlook remains bleak for the early months of 2021: For now, most cruise lines have canceled all sailings into May or June.

Long-distance car travel, before and during the pandemic

Driving trips at least 50 miles from home, with stays of two hours or more, based on a daily index from

mobile location data.

Trips at least 50 miles from home, with stays of two hours

or more, based on a daily index from mobile location data.

Air travel, both international and domestic, was markedly curtailed by the pandemic. But how was car travel affected?

One way to measure the change is to look at the Daily Travel Index compiled by Arrivalist , a company that uses mobile location data to measure consumer road trips of 50 miles or more in all 50 U.S. states.

The figures tell the story of a rebound that’s slightly stronger than that of air travel: a sharp drop in March and April, as state and local restrictions fell into place , followed by a gradual rise to around 80 percent of 2019 levels.

Difference in visits to four popular national parks, 2019 to 2020

1.0 MILLION

GREAT SMOKY

GRAND CANYON

CUYAHOGA VALLEY

YELLOWSTONE

1.0 million

Another way to consider car travel in 2020 — and domestic travel in the U.S. more broadly — is to look at the visitation numbers for America’s national parks.

Over all, national park visitation decreased by 28 percent in 2020 — to 237 million visitors, down from 327.5 million in 2019, largely because of temporary park closures and pandemic-related capacity restrictions.

The caveat, though, is that several parks saw record numbers of visitors in the second half of the year, as a wave of travel-starved tourists began looking for safe and responsible forms of recreation.

Consider the figures for recreational visits at Yellowstone National Park. After a shutdown in April, monthly visitation at the park quickly rose above 2019 levels. The months of September and October of 2020 were both the busiest on record, with numbers in October surpassing the previous monthly record by 43 percent .

Some national parks located near cities served as convenient recreational escapes throughout the pandemic. At Cuyahoga Valley National Park, 2020 numbers exceeded 2019 numbers from March through December. At Great Smoky Mountains National Park, numbers surged after a 46-day closure in the spring and partial closures through August; between June and December, the park saw one million additional visits compared to the same time period in 2019.

Stephen Hiltner is an editor on the Travel desk. You can follow his work on Instagram and Twitter . More about Stephen Hiltner

Come Sail Away

Love them or hate them, cruises can provide a unique perspective on travel..

Cruise Ship Surprises: Here are five unexpected features on ships , some of which you hopefully won’t discover on your own.

Icon of the Seas: Our reporter joined thousands of passengers on the inaugural sailing of Royal Caribbean’s Icon of the Seas . The most surprising thing she found? Some actual peace and quiet .

Th ree-Year Cruise, Unraveled: The Life at Sea cruise was supposed to be the ultimate bucket-list experience : 382 port calls over 1,095 days. Here’s why those who signed up are seeking fraud charges instead.

TikTok’s Favorite New ‘Reality Show’: People on social media have turned the unwitting passengers of a nine-month world cruise into “cast members” overnight.

Dipping Their Toes: Younger generations of travelers are venturing onto ships for the first time . Many are saving money.

Cult Cruisers: These devoted cruise fanatics, most of them retirees, have one main goal: to almost never touch dry land .

UN Tourism | Bringing the world closer

Secretary-general’s policy brief on tourism and covid-19.

share this content

- Share this article on facebook

- Share this article on twitter

- Share this article on linkedin

Tourism and COVID-19 – unprecedented economic impacts

The Policy Brief provides an overview of the socio-economic impacts from the pandemic on tourism, including on the millions of livelihoods it sustains. It highlights the role tourism plays in advancing the Sustainable Development Goals, including its relationship with environmental goals and culture. The Brief calls on the urgency of mitigating the impacts on livelihoods, especially for women, youth and informal workers.

The crisis is an opportunity to rethink how tourism interacts with our societies, other economic sectors and our natural resources and ecosystems; to measure and manage it better; to ensure a fair distribution of its benefits and to advance the transition towards a carbon neutral and resilient tourism economy.

The brief provides recommendations in five priority areas to cushion the massive impacts on lives and economies and to rebuild a tourism with people at the center. It features examples of governments support to the sector, calls for a reopening that gives priority to the health and safety of the workers, travelers and host communities and provides a roadmap to transform tourism.

- Tourism is one of the world’s major economic sectors. It is the third-largest export category (after fuels and chemicals) and in 2019 accounted for 7% of global trade .

- For some countries, it can represent over 20% of their GDP and, overall, it is the third largest export sector of the global economy.

- Tourism is one of the sectors most affected by the Covid-19 pandemic, impacting economies, livelihoods, public services and opportunities on all continents. All parts of its vast value-chain have been affected.

- Export revenues from tourism could fall by $910 billion to $1.2 trillion in 2020. This will have a wider impact and could reduce global GDP by 1.5% to 2.8% .

- Tourism supports one in 10 jobs and provides livelihoods for many millions more in both developing and developed economies.

- In some Small Island Developing States (SIDS), tourism has accounted for as much as 80% of exports, while it also represents important shares of national economies in both developed and developing countries.

100 to 120 MILLON

direct tourism jobs at risk

Massive Impact on Livelihoods

- As many as 100 million direct tourism jobs are at risk , in addition to sectors associated with tourism such as labour-intensive accommodation and food services industries that provide employment for 144 million workers worldwide. Small businesses (which shoulder 80% of global tourism) are particularly vulnerable.

- Women, who make up 54% of the tourism workforce, youth and workers in the informal economy are among the most at-risk categories.

- No nation will be unaffected. Destinations most reliant on tourism for jobs and economic growth are likely to be hit hardest: SIDS, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and African countries. In Africa, the sector represented 10% of all exports in 2019.

US$ 910 Billon to US$ 1.2 Trillon

in export from tourism - international visitors' spending

Preserving the Planet -- Mitigating Impacts on Nature and Culture

- The sudden fall in tourism cuts off funding for biodiversity conservation . Some 7% of world tourism relates to wildlife , a segment growing by 3% annually.

- This places jobs at risk and has already led to a rise in poaching, looting and in consumption of bushmeat , partly due to the decreased presence of tourists and staff.

- The impact on biodiversity and ecosystems is particularly critical in SIDS and LDCs. In many African destinations, wildlife accounts for up to 80% of visits, and in many SIDS, tourism revenues enable marine conservation efforts.

- Several examples of community involvement in nature tourism show how communities, including indigenous peoples, have been able to protect their cultural and natural heritage while creating wealth and improve their wellbeing. The impact of COVID-19 on tourism places further pressure on heritage conservation as well as on the cultural and social fabric of communities , particularly for indigenous people and ethnic groups.

- For instance, many intangible cultural heritage practices such as traditional festivals and gatherings have been halted or postponed , and with the closure of markets for handicrafts, products and other goods , indigenous women’s revenues have been particularly impacted.

- 90% of countries have closed World Heritage Sites, with immense socio-economic consequences for communities reliant on tourism. Further, 90% of museums closed and 13% may never reopen.

1.5% to 2.8 of global GDP

Five priorities for tourism’s restart.

The COVID-19 crisis is a watershed moment to align the effort of sustaining livelihoods dependent on tourism to the SDGs and ensuring a more resilient, inclusive, carbon neutral, and resource efficient future.

A roadmap to transform tourism needs to address five priority areas:

- Mitigate socio-economic impacts on livelihoods , particularly women’s employment and economic security.

- Boost competitiveness and build resilience , including through economic diversification, with promotion of domestic and regional tourism where possible, and facilitation of conducive business environment for micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs).

- Advance innovation and digital transformation of tourism , including promotion of innovation and investment in digital skills, particularly for workers temporarily without jobs and for job seekers.

- Foster sustainability and green growth to shift towards a resilient, competitive, resource efficient and carbon-neutral tourism sector. Green investments for recovery could target protected areas, renewable energy, smart buildings and the circular economy, among other opportunities.

- Coordination and partnerships to restart and transform sector towards achieving SDGs , ensuring tourism’s restart and recovery puts people first and work together to ease and lift travel restrictions in a responsible and coordinated manner.

a lifelive for

SIDS, LDCs and many AFRICAN COUNTRIES

tourism represents over 30% of exports for the majority of SIDS and 80% for some

Moving Ahead Together

- As countries gradually lift travel restrictions and tourism slowly restarts in many parts of the world, health must continue to be a priority and coordinated heath protocols that protect workers, communities and travellers, while supporting companies and workers, must be firmly in place.

- Only through collective action and international cooperation will we be able to transform tourism, advance its contribution to the 2030 Agenda and its shift towards an inclusive and carbon neutral sector that harnesses innovation and digitalization, embraces local values and communities and creates decent job opportunities for all, leaving no one behind. We are stronger together.

RESOURCES FOR CONSEVATION

of natural and cultural heritage

Related links

- Policy Brief: Tourism and COVID-19

- The Impact of COVID-19 on Tourism

- António Guterres - Video

- Press Releases

- Press Enquiries

- Travel Hub / Blog

- Brand Resources

- Newsletter Sign Up

- Global Summit

- Hosting a Summit

- Upcoming Events

- Previous Events

- Event Photography

- Event Enquiries

- Our Members

- Our Associates Community

- Membership Benefits

- Enquire About Membership

- Sponsors & Partners

- Insights & Publications

- WTTC Research Hub

- Economic Impact

- Knowledge Partners

- Data Enquiries

- Hotel Sustainability Basics

- Community Conscious Travel

- SafeTravels Stamp Application

- SafeTravels: Global Protocols & Stamp

- Security & Travel Facilitation

- Sustainable Growth

- Women Empowerment

- Destination Spotlight - SLO CAL

- Vision For Nature Positive Travel and Tourism

- Governments

- Consumer Travel Blog

- ONEin330Million Campaign

- Reunite Campaign

Economic Impact Research

- In 2023, the Travel & Tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP; an increase of 23.2% from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 level.

- In 2023, there were 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level.

- Domestic visitor spending rose by 18.1% in 2023, surpassing the 2019 level.

- International visitor spending registered a 33.1% jump in 2023 but remained 14.4% below the 2019 total.

Click here for links to the different economy/country and regional reports

Why conduct research?

From the outset, our Members realised that hard economic facts were needed to help governments and policymakers truly understand the potential of Travel & Tourism. Measuring the size and growth of Travel & Tourism and its contribution to society, therefore, plays a vital part in underpinning WTTC’s work.

What research does WTTC carry out?

Each year, WTTC and Oxford Economics produce reports covering the economic contribution of our sector in 185 countries, for 26 economic and geographic regions, and for more than 70 cities. We also benchmark Travel & Tourism against other economic sectors and analyse the impact of government policies affecting the sector such as jobs and visa facilitation.

Visit our Research Hub via the button below to find all our Economic Impact Reports, as well as other reports on Travel and Tourism.

- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2021

The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis

- Haroon Rasool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0083-4553 1 ,

- Shafat Maqbool 2 &

- Md. Tarique 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

119k Accesses

85 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

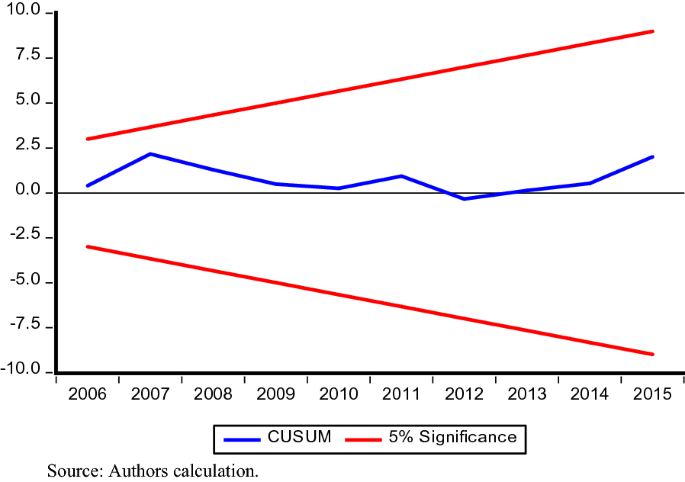

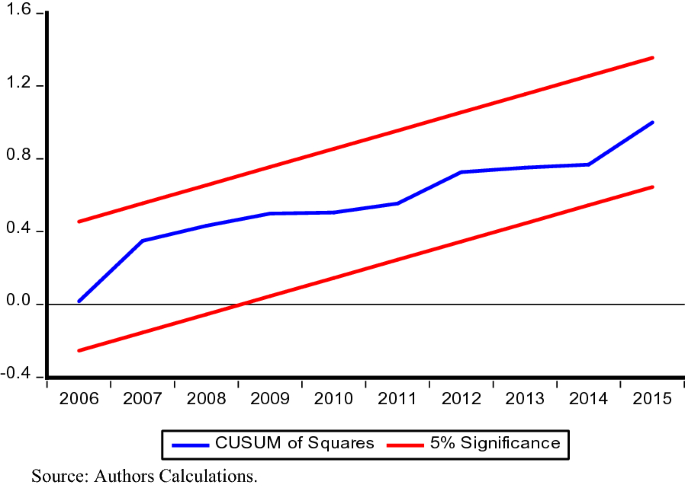

Tourism has become the world’s third-largest export industry after fuels and chemicals, and ahead of food and automotive products. From last few years, there has been a great surge in international tourism, culminates to 7% share of World’s total exports in 2016. To this end, the study attempts to examine the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth by using the panel data over the period 1995–2015 for five BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries. The results of panel ARDL cointegration test indicate that tourism, financial development and economic growth are cointegrated in the long run. Further, the Granger causality analysis demonstrates that the causality between inbound tourism and economic growth is bi-directional, thus validates the ‘feedback-hypothesis’ in BRICS countries. The study suggests that BRICS countries should promote favorable tourism policies to push up the economic growth and in turn economic growth will positively contribute to international tourism.

Introduction

World Tourism Day 2015 was celebrated around the theme ‘One Billion Tourists; One Billion Opportunities’ highlighting the transformative potential of one billion tourists. With more than one billion tourists traveling to an international destination every year, tourism has become a leading economic sector, contributing 9.8% of global GDP and represents 7% of the world’s total exports [ 59 ]. According to the World Tourism Organization, the year 2013 saw more than 1.087 billion Foreign Tourist Arrivals and US $1075 billion foreign tourism receipts. The contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to reach 10.8% at the end of 2026 [ 61 ]. Representing more than just economic strength, these figures exemplify the vast potential of tourism, to address some of the world´s most pressing challenges, including socio-economic growth and inclusive development.

Developing countries are emerging as the important players, and increasingly aware of their economic potential. Once essentially excluded from the tourism industry, the developing world has now become its major growth area. These countries majorly rely on tourism for their foreign exchange reserves. For the world’s forty poorest countries, tourism is the second-most important source of foreign exchange after oil [ 37 ].

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries have emerged as a potential bloc in the developing countries which caters the major tourists from developed countries. Tourism becomes major focus at BRICS Xiamen Summit 2017 held in China. These countries have robust growth rate, and are focal destinations for global tourists. During 1990 to 2014, these countries stride from 11% of the world’s GDP to almost 30% [ 17 ]. Among BRICS countries, China is ranked as an important destination followed by Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa [ 60 ].

The importance of inbound tourism has grown exponentially, because of its growing contribution to the economic growth in the long run. It enhances economic growth by augmenting the foreign exchange reserves [ 38 ], stimulating investments in new infrastructure, human capital and increases competition [ 9 ], promoting industrial development [ 34 ], creates jobs and hence to increase income [ 34 ], inbound tourism also generates positive externalities [ 1 , 14 ] and finally, as economy grows, one can argue that growth in GDP could lead to further increase in international tourism [ 11 ].

The tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) proposed by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda [ 3 ], states that expansion of international tourism activities exerts economic growth, hence offering a theoretical and empirical link between inbound tourism and economic growth. Theoretically, the TLGH was directly derived from the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) that postulates that economic growth can be generated not only by increasing the amount of labor and capital within the economy, but also by expanding exports.

The ‘new growth theory,’ developed by Balassa [ 4 ], suggests that export expansion can trigger economic growth, because it promotes specialization and raises factors productivity by increasing competition, creating positive externalities by advancing the dispersal of specialized information and abilities. Exports also enhance economic growth by increasing the level of investment. International tourism is considered as a non-standard type of export, as it indicates a source of receipts and consumption in situ. Given the difficulties in measuring tourism activity, the economic literature tends to focus on primary and manufactured product exports, hence neglecting this economic sector. Analogous to the ELGH, the TLGH analyses the possible temporal relationship between tourism and economic growth, both in the short and long run. The question is whether tourism activity leads to economic growth or, alternatively, economic expansion drives tourism growth, or indeed a bi-directional relationship exists between the two variables.

To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. Financial markets are considered a key factor in producing strong economic growth, because they contribute to economic efficiency by diverting financial funds from unproductive to productive uses. The origin of this role of financial development may is traced back to the seminal work of Schumpeter [ 50 ]. In his study, Schumpeter points out that the banking system is the crucial factor for economic growth due to its role in the allocation of savings, the encouragement of innovation, and the funding of productive investments. Early works, such as Goldsmith [ 18 ], McKinnon [ 39 ] and Shaw [ 51 ] put forward considerable evidence that financial development enhances growth performance of countries. The importance of financial development in BRICS economies is reflected by the establishment of the ‘New Development Bank’ aimed at financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in these and other developing countries. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no attempt has been made so far to investigate the long-run relationship Footnote 1 between tourism, financial development and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Hence, the present study is an attempt to fill the gap in the existing literature.

Review of past studies